A recent law journal essay referenced on this site examined Digital Rights Management and its impact on the e-book industry.

DRM, the essay said, is counter to the precepts of open-source development in computer hardware and software, thereby hindering innovation and slowing technological progress in the e-book industry.

The implicit assumption is that open-source is good for innovation in the computer industry in general, and especially in the e-book industry. But is it? Has open source been a positive influence on e-book development? Or has open source itself hindered the progress of e-books, DRM notwithstanding?

Open source’s impact

The development of the computer industry in general has been spearheaded by open-source development. Open platforms do inspire innovation; and in the computer industry, that innovation has given us multiple programming languages, multiple operating systems, parallel applications by major corporations and individual programmers, and a horde of independent programmers and debuggers, free to work on any aspect of computing that interests them.

In the e-book industry, lack of commitment by the major players, i.e. the publishing industry, has resulted in open source believers attempting to take the reins in their own hands. This has similarly resulted in more e-book formats, e-book reading software and DRM-type security systems than can be reliably counted, and as those programmers have changed their focuses and moved on to new projects over the years, many of these formats have gone orphaned, leaving many customers with unsupported e-books and e-book reading applications.

The problems with orphaned e-books and software have resulted in a significant number of early-adopters abandoning e-books, for fear of losing money and purchased products down the line. Even before DRM had driven e-book enthusiasts away, orphaned formats had already done the damage of making users and publishers alike leery of the industry in general.

In contrast, the electronic music industry started down a similar path, but veered off quickly: At the time that different open source formats were being experimented with, a single format (MP3) was developed and quickly adopted by the majority of music listeners for its combination of portable size, ease of recording and sound quality. Once MP3 was locked in as the default music format, companies were free to develop compatible business models as enthusiasts were free to create their own music. Less time and money was wasted on other formats that would eventually die off and leave users hanging. Innovation became in fact more directed and focused, and resulted in a viable industry and financial model in a relatively short time.

Now, as major corporations try to finally take charge in the literature industry, and publishers try to insert themselves into an aspect of their own industry that almost passed them by, the confusing variety of open-source-created e-book formats, conversion programs and DRM blockers (mostly made available so people could convert from one open-source format to another), has created the “Tower of e-Babel” that has brought e-book development to an embarrassingly slow crawl. Developer’s resources are spread too thin, players are afraid to innovate for fear of becoming orphaned in a churning market, and interested parties are afraid to invest. In this case, open-source has been a clear and severe hindrance to the development of e-books.

Result

Following this logic, it would be understandable to say DRM has not hurt e-books as much as open source development itself has. Badly-executed DRM systems can hardly be said to be good for the industry… but because of adverse effects on customers, not for stifling of innovation. The overwhelming stifling of e-book innovation is being caused by an unfocused, foggy, misdirected, every-man-for-himself open source melee. The e-book industry needs to end the churn and refine its direction and focus, in order to progress properly and efficiently.

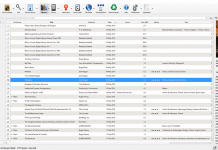

The present efforts in the e-book industry are managing to whittle down the formats to a standardized few: Mobipocket, through Amazon; eReader, through Barnes & Noble; and OEB (ePub), developed as a standard format by the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF) and supported by Adobe, Sony and many other reading device and software manufacturers. As formats dwindle, players and potential players will gain optimism for the more stable market and feel more empowered to buy, invest and innovate. Said innovation will likely happen through licensed channels and more formal agreements, not the intention of open source; but it is more likely to be carried out by more capable individuals and organizations, and result in more rigorous and effective innovation.

Speculation

Suppose the whittling down of formats had happened years ago, early in e-books’ development as it did in digital music? Going by the development of digital music as a guide, today we would probably have a few dozen different reading applications, some of which would be created by corporations, and some by open-source programmers, capable of running the one or two major formats that would be dominant in the industry, with a variety of optional tools and controls to allow individual users to customize their viewing experience. They would be available for every operating system, on computers large and small. All of these applications would be able to read the same DRM’d e-books, largely eliminating the need to crack DRM for most consumers. But there would still be a number of open-source DRM cracking tools, some of which might even be built into the open-source reading applications, allowing consumers to transfer their e-books to other personal devices and/or storage options.

This is the direction the e-book industry should have progressed; and would have, if open-source efforts had not so badly fractionalized the industry early-on. As we bring our range of e-book formats down, undoing the damage caused by open-source fractionalization, we can expect to see exactly this sort of development to happen, as it did to the digital music industry, and we will end up with a healthy e-book industry.

This claim is not, in fact, an effort to support DRM or unworkable security systems in e-books. Rather, it is an effort to point the accusing finger in the proper direction: DRM has not been the real damaging factor in the e-book industry; the open-source movement itself has been the real cause of hindered innovation and slow development.

For a given eBook, we used to create five formats: PDF, LIT, Palm/eReader, Sony BBeB, and Mobipocket. I don’t think I’d describe any of those as open source (although PDF is officially an open standard). Now we just do ePub.

So what open-source formats are you talking about? And how has the open-source movement hurt eBooks? Most of the formats and readers I’m aware of are proprietary, and you seem to be identifying the multiplicity of formats and reading systems with the open-source software movement, without really explaining why.

I appreciate Teleread’s willingness to post divergent views. But this is just dim. Comparing DRM – locks on a file – with standards (the structure of the file) is … odd.

Many of those abandoned formats that you believe have contributed to slower ebook adoption are actually proprietary formats. Certainly most of the ones that were ever commercially viable. If there’s an ebook tower of babel it is almost certainly built of proprietary formats.

It would help to have more specifics. Can you point to specific examples of what you have described as the “unfocused, foggy, misdirected, every-man-for-himself open source melee”?

Also, I would point out that outside of the ebook — but during the same time frame that open source was allegedly holding ebooks back — we’ve seen an explosion of digital publishing on the web, all of which has been based entirely on open source.

This would have been closer to correct if “open source” was replaced by “closed source” or even “free market”. It is DRM and closed source readers that have created the multitude of formats. Probably the two most popular Open Source ebooks applications today are Calibre and FBReader. Neither one supports DRM, and in fact if an Open Source ebook app in the US included DRM its developers would go directly to Federal Prison. Both Calibre and FBReader support multiple ebook formats, and supporting multiple formats isn’t rocket science if the formats are a) DRM-free and b) documented. It is closed source and the free market, backed up by laws like the DMCA, that create multiple undocumented ebook formats, each hiding behind its own DRM bastion. These become orphans when the company that developed the closed source reader decides that there isn’t enough profit in those old ebooks. Note that both Adobe and Amazon have ditched DRM-ridden ebooks in the past, so it isn’t just bankruptcy that we have to worry about.

Pretending the music industry rallied around MP3 is hilarious, not to mention a complete re-write of history. Putting aside all the failed DRM’ed formats littering the music landscape (and people’s hard drives), the most successful digital music story by far is the Apple iTunes Store, which came to power selling DRMed music, and only recently moved to DRM free music-neither of which were or are in “MP3” format.

Claiming that the digital music industry succeeded quickly by rallying around MP3 is also just plain wrong. It was a long, tedious, lawsuit filled battle that is still being fought.

Besides the flaws in Steve’s arguments that have already been pointed out, Steve missed another important point. It is probably true that the majority of digital music is encoded in the mp3 format, however, the most successful music store, iTunes, actually uses ACC as its format of choice. In other words, MP3 is the choice of those who rip their CDs, or who download from the file sharing sites, not necessarily the standard adopted by the industry.

Ultimately, closed source software is more likely to code proprietary add ons (such as Adobe DRM to the ePub standard) which is what really leaves customers vulnerable to being orphaned. If an open format really gains traction, it is rare, that it will be orphaned by the open source community (if for no other reason than companies will start investing in the format).

This article is just rubbish; it is on a level with Steve’s statement in “Why is this Hill so Steep” that Bill Gates worked for IBM. Just plain wrong. (Boy, I’m glad I didn’t spend $4.00 on that book!)

There is no attempt to differentiate between open source as it applies to reading software, the underlying OS, or the book formats themselves. Steves just refers to this nebulous thing called open source (and it is bad).

I’d argue that the fact that the OS that most reading hardware runs is open source and effectively free makes the cost of these devices much lower than if a proprietary OS had to be developed or licensed. How does that hinder ebook development?

Steve does not give any examples of any of his imagined multitude of orphaned open source formats. Not even one.

For example, he promotes Mobipocket as being a format saved by Kindle, when in fact the Kindle used an incompatible version of Mobipocket and now has effectively killed the original. That’s not open source orphaning formats, that is vested commercial interests destroying it – in an attempt to build an artificial ecosystem to promote their own goals.

He’s even wrong about how rosy everything was in the digital music arena; Sony tried for years to promote their hideous ATRAC format, and wouldn’t even permit mp3 compatibility on their devices for many years until they eventually gave up. They’ve never recovered from those mistakes.

Orphaned formats really aren’t a big deal if DRM doesn’t prevent format shifting. Formats have of necessity evolved as the industries understanding of what is required functionality in ebooks has matured.

Open source has absolutely nothing to do with this.

As Co-Editor of this blog, David’s disclaimer on this post does not imply that I agree with David’s view as to “TeleRead’s opinion”.

DRM, not open source, is the real eBabel villain, and I thank the TeleRead community members who spoke up and explained why. Vendors use DRM as a gotcha. We already have the ePub standard. Without DRM tainting the industry, outfits like FBReader would really go to town, and we’d see a zillion apps available for reading best-sellers in the nonproprietary ePub format. DRM turns nonproprietary ePub files into eBabel and prevents format shifting

While Steve articulately expressed his side, I’d respectfully disagree.

Simply in the interest of the smooth running of the site—and not as a retreat from my own strong preference for an open approach—I removed the disclaimer and am substituting this comment.

Thanks,

David

I think this person is blaming the wrong thing for the present splintering of the ebook world. I personally think that the youth of the industry is what has caused this fragmentation. It’s the wild west right now, and everyone is running to stake their claim with their own format. As time progresses, formats will die off (many are already functionally dead), as this person has said himself. The same story could be told for DRM.

I really can’t think of any way “open source” has particularly impacted ebooks. Even Project Gutenberg isn’t “open source”. I think the term “open source” is being thrown around carelessly and used in places were it actually doesn’t apply.

hello i am sachin dhawan and i am doing a course of gniit from niit institute and open source is my project.open source is a very very good thing

A couple of small corrections here:

MP3 is not an open format, but a closed, licensed, proprietary one. Part of what made mp3 succeed as the de facto standard was that the Fraunhofer Institute’s licensing for mp3 players was to make it free for players, and cost money to encode (I think). This meant that IIRC companies like MusicBox could release free players to all us users, which helped us all standardize on that format.

Microsoft’s .lit, epub, mobipocket, and some other formats are all based on the open standard of html. So is Amazon’s kindle format. In that sense, ebooks have indeed finalized on one format, though it is wrapped in different and proprietary enclosures and binaries, with proprietary DRM frosting. FBReader does a great job displaying plain-vanilla html files as ebooks on the various platforms to which FBReader has been ported.

As others have noted, ebook devices are mostly running open source OS: Kindle on Linux, Nook on Android (a Linux variant), iPhone on BSD (ultimately). The Hanlin devices all run Linux variants. I wonder whether we would have a Kindle today if not for open source software.

This is a provocative, thought-inducing post, raising a good question, although alas it reaches the wrong answer.

Another approach to format diversity is presented by the print book. In print there are 100’s of formats, but only one device. E-books are not likely to trend toward that solution since the device rather than the content represents the proprietary commodity. A given title is exclusive, although accessed from various devices, due to exclusivity of the device, not due to format exclusivity characteristic of various print editions of a given title.

Boy… for a speculative piece, that one seems to be pissing off a lot of people.

Without simply backing off on anything I said, I can only say that the piece was dashed off quickly, while on vacation (and probably lubricated by a tad too much rum), and posted by me… just to hear the responses. I was not in the proper frame of mind when I wrote the piece. I was actually trying to make a good point… and it all came out way wrong in execution.

So, I’m not a saint. Mea culpa. But I’ll endeavor not to do it again, and I’ll just fade away now and let everyone enjoy their holidays.

It seems like the core thesis of this article is: More file formats is bad for innovation. Well, if we were to stick with .txt file format, that would be more efficient for everyone implementing it, we’re done. But we’re not talking about the cost of implementing a device that supports enough formats to be valuable, we’re talking about innovation. I would argue that developing “NOVEL” formats could be seen as innovation, especially if they solve formatting, language, etc. problems in interesting ways. If you diffuse the formats (through commercialization or other means), that makes the novelty an innovation.

The author of the original essay writes:

““Open-source DRM” is a contradiction in terms, for open source encourages user modification (and copyleft requires its availability), while DRM compels “robustness” against those same user modifications.”

Clearly there’s a difference between having source code available of a DRM scheme that is implemented on your device and having the means to modify the firmware running on an e-reader device to circumvent this. So there’s no reason for a contradiction between Open Source and DRM. It is possible and has been implemented:

http://www.wired.com/entertainment/music/commentary/listeningpost/2006/04/70548

And the article above also seems to confuse open source and open standards.

All in all, a gripping theme, but it looks like it was written in a hurry and with too much rum… Oh wait, it was! (see the post above)