![image164[1] image164[1]](http://www.teleread.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/image1641_thumb.png) The New Yorker has a great in-depth piece on the three-way power struggle involving Amazon, Apple, and Google around the “big six” publishers. There may not be much new to people who closely followed the last several months of e-book news, but there is a certain value in seeing all that history together in one place. It makes a good primer for those who might not have been paying that much attention.

The New Yorker has a great in-depth piece on the three-way power struggle involving Amazon, Apple, and Google around the “big six” publishers. There may not be much new to people who closely followed the last several months of e-book news, but there is a certain value in seeing all that history together in one place. It makes a good primer for those who might not have been paying that much attention.

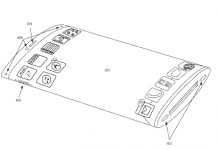

The article covers publishers’ discomfiture with Amazon’s $9.99 price point, the institution of agency pricing and Amazon’s temper tantrum, and the launch of the iPod and iBooks. It also mentions Google’s plan for its own bookstore once the settlement with the Authors Guild is straightened out.

It goes into detail on Amazon’s plans to act as a publisher itself—and the unhappiness of traditional publishers at the idea that Amazon might replace them.

The article also notes that there is no guarantee the agency pricing Apple instituted will continue—Apple only agreed to it for one year, and has a history of trying to lower prices.

(Found via BoingBoing.)

From the article:

“On a twenty-six-dollar book, the publisher receives thirteen dollars, out of which it pays all the costs of making the book. The author gets $3.90 in royalties. Bookstores return about forty per cent of the hardcovers they buy; this accounts for $5.20 per book. Another $3 goes to overhead costs and the price of producing and shipping the book—leaving, in the best case, about a dollar of profit per book.”

Foul!

The publisher in not out $5.20 per book because of returned books. They get the book back and can sell it somewhere else. Profit per book: $6.20, or 24%.

1- Wrapping overhead into the cost of producing the book is a typical profit-hiding trick and inflating ebook costs since a properly-run operation would not incur any added costs in producing the ebook.

2- With no returns to impact the ebook, their margin on the ebook (smoke-and-mirrors overhead notwithstanding) would run close to 50%, no?

I agree that the publishers have Been obfuscating for too long. Their profit margins are a bit more robust then they like to publicly state. I am not surprised that the publishers’ puppet mag “publishers’ lunch” would go after the new yorker piece. Like I said in an earlier piece the new head gurus dominating the ebook world have no interest servicing readers.

@Bruce Wilson:

Publishers don’t get ‘returned’ books back for resale. A bookstore returns a book by ripping off its cover, shredding the rest, and sending the cover back to the publisher for credit.

The issue with returns is that in addition to the wasted printing and shipping costs, the amortization of the fixed costs (pre-publication, promotion, and oftentimes author royalty advances) has to be spread over fewer sold copies. Most of the cost numbers really need to be calculated on ‘books sold’ rather than ‘books printed’.

@Doug: That might be true for paperbacks, but hardbound books do tend to return to the publisher, then be farmed out to the overstock merchants who then put them on discount tables at Waldenbooks, Big Lots, and other discount venues.

@Bruce Wilson:

I stand corrected.

@Doug: Out of curiosity, why do you keep calling me “Bruce Wilson”?

@Chris Meadows:

From not paying attention. Bruce was the one I’d originally responded to and I just copied that part down to my second response. Been a long day. 🙂

What’s with the vitriol against publishers? I understand that democratization through the internet has brought on an intense desire for every user’s thoughts to be heard equally, well-stated or not, and also the belief that information should be virtually free–but these attitudes towards publishers are curiously vindictive.

As for the costs of a book: the ‘production’ of a book is not merely its binding and paper printing, which, I give you, is the overhead. The production costs reach beyond basic the printing and binding overhead to include the cover artists, the editorial input on covers, the copywriters for the jackets, the typographers–and that’s all before actual overhead of printing and shipping. Do you want to talk about the other myriad people involved in acquiring a book, editing it, publicizing it, and marketing it? No, you don’t. Because then you would have to acknowledge that a book is worth more than $9.99. And then also acknowledge you don’t want a world without a publishing industry–as flawed as the current system might be.

The cost of making a successful book is not nearly so small as that of a music album, for instance, which now can be both made and distributed successfully by one single musician, and listened to in a matter of 30 minutes. Meanwhile, the successful creation of a single book in today’s market requires no less than a dozen (might I add very poorly paid–not takin’ 3-martini lunches here) people to create and sell.

While we like to think we all ‘deserve’ information and ideas cheaply or for free, we’re talking about cultural capital here–not just a product, whether it’s digital or non-digital. The fight isn’t “publisher vs. customer”, folks. The fight is between a future with reading versus a future without reading. And I, for one, hope the former wins.

@Angela: The “vitriol” against the Big Publishing Houses is of recent vintage. It has a wee bit to do with the recent overnight 30% ebook price hike that was first publicly announced (In a public forum, no less) to *insiders* as essentially a way to squeeze more money out of consumers.

To a lot of folks the message and the context read like a declaration of war and they responded appropriately.

Since then, the BPHs have engaged in a belated woe-is-me campaign trotting out a variety of laughable excuses to try to justify the money grab.

(The most recent, which has lead to a rash of laughter-induced injuries, is the claim that the ebook price hike is intended to “save” brick and mortar bookstores. Which, considering that the BPHs’ volume-discount pricing policies over the last 20 years are the primary direct cause for the decimation of the B&M bookstores in the first place, explains the rash of emergency room visits due to strained ribcage muscles.)

The issue isn’t publishers in general, its the five specific companies who seem hellbent on commiting suicide and dragging their authors with them.

That said, make no mistake: reading in the 21st century is in no danger of extinction. The giant horizontal-sprawl BPH dinosaurs are dying of self-inflicted wounds but the publishing industry as a whole is actually quite healthy. Don’t buy the tales of woe of the BPHs; what we are seeing is a migration of readership from the 19th century publishing Oligarchs to the mid-size and small independent publishers who understand things like modern document-management technology, viral marketting and, oh, yes, that oh-so-new concept of customer support.

And if the BPHs can’t make a book profitably in the current environment, rest assured there are plenty of other publishers that can and *are* doing fine.

We are in the midst of a technological market disruption, much as other industries have gone through. History has shown that those disruptions only kill those companies that cling to the past; companies that adjus to the new rules prosper.

Forgive me if I have little sympathy for those willing to go down with a sinking ship while a fleet of empty lifeboats beckons.

Angela,

The first aspects you mentioned:

“The production costs reach beyond basic the printing and binding overhead to include the cover artists, the editorial input on covers, the copywriters for the jackets, the typographers–and that’s all before actual overhead of printing and shipping.”

All these first factors you mentioned don’t factor into the e-book-pricing wars and consumers are not interested in paying more for e-books to prop up badly managed hard-cover sales (meaning unrealistic projections and costs based upon those) or brick & mortar stores as they say.

I am a member of Barnes and Noble, because I do love to go visit a place with physical books (other than the library).

But the Big5 publishers are, at the least, unwise, and ‘suicidal’ as someone else said to even imagine that consumers will pay hiked-up pricing for digital copies we can’t lend or give away just so they can compensate for smaller gains from their preferred hardcover sales. It’s a new world and they have to adjust their way of operating for it.