Welcome to Court Merrigan, our latest contributor. A writer in Thailand, he writes the Endless Emendation blog. – D.R.

Welcome to Court Merrigan, our latest contributor. A writer in Thailand, he writes the Endless Emendation blog. – D.R.

Imagine it is 1991. Your task is to produce the greatest reference work in history. It must cover everything from the best Thai food in Durham to the history of the Blue Dog coalition. Will you hire an army of experts and editors to produce an encyclopedia? Or will you wait for an unorganized multitude of volunteers aided by search engines to create a world wide web of information?

I would have bet on the experts. James Boyle, Duke University law professor and author of The Public Domain, would have, too (free download from Boyle, Feedbooks and Manybooks; buying info here).

I would have bet on the experts. James Boyle, Duke University law professor and author of The Public Domain, would have, too (free download from Boyle, Feedbooks and Manybooks; buying info here).

The last time he consulted a print encyclopedia was 1998. You? The Internet, of course, changed everything. But: “In the middle of the most successful and exciting experiment in nonproprietary, distributed creativity in the history of our species, our policy makers can see only the threat from ‘piracy.'”

Take an MP3. Boyle argues that it is fundamentally different than physical property, like a car. My use of an MP3 does not interfere with yours. We can both listen to it. No property is lost if it is copied or shared. It is not like stealing your car. You have an MP3, and I have an MP3. No one has “lost” anything. Except the content provider’s (an insidious term if ever there was one) opportunity for profit. BMG and Sony, naturally, equate file-sharing with theft. They argue that file-sharing means no creators are compensated, meaning there is no incentive to create. No one creates for free, they say. A one-word retort: Wikipedia.

The recording companies use copyright law to protect their ability to profit in a specific, proprietary way. But as Boyle points out, the very purpose of copyright law is not to protect creators, and still less distributors, but to insure that the public receives the benefit of new creativity through the incentives of a free market. Hence, the public domain: work enters the public domain after a reasonable period so anyone can build on it. But not to hear BMG or Hollywood tell it. They’re busy putting up digital barbed wire across the free range of the Internet to “protect” their content. This despite their own history of flawed predictions. VCRs were once declared the death knell for Hollywood. Attempts were made to smother home video technology in its cradle.

And yet today Hollywood thrives off movie rentals

Boyle argues the same holds true with the Internet. Fortunately for us, the technology simply evolved too fast. Had policy makers and content providers been given the opportunity, they would surely have killed the Internet as we know it. Remember AOL, circa 1995? That’s where the content providers were comfortable. They are doing their best not to drop the ball again. Boyle marshals a series of powerful arguments ranging from Thomas Jefferson to Ray Charles to Google to show why they must be stopped. We began to lock up our culture “at the very moment in history when the Internet made it a particularly stupid idea to do so”, and the tide must be reversed.

Boyle ends The Public Domain with a call for “cultural environmentalism” to protect and expand the public domain. I like all that the idea conjures up, but I was left a little unclear as to how it could happen. Boyle treads over highly analytical and technical issues with a light touch, but not light enough. Carefully endnoted evidence abounds, emotive talk is eschewed in favor of provisional conclusions based upon empirical evidence. Fair enough, but that approach isn’t likely to start any grassroots fires. The broad-based popular movement Boyle envisions requires a Silent Spring moment. Most readers will find this fine book a touch wonkish to tug their heartstrings.

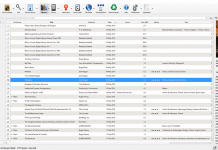

Appropriately, the “internet range wars” extend to this very book. I downloaded it free as a PDF file. As my Kindle does not support PDF, Amazon will convert it to their proprietary .azw file. (Every Kindle owner has free access to this very useful – if totally unnecessary – service.) The formatting is somewhat ragged although still eminently readable. The Kindle’s notetaking and highlighting functions are a touch cumbersome and involve waiting for a lot of screens and windows and some awkward keying on tiny buttons. True enough, your notes, highlights and bookmarks are saved – but only as long as you keep it on your Kindle. At this point, I’m not sure whether this represents much of an advance over margin notes, a highlighter, and scribbles in a notebook.

But it could. If there were a standard e-book format, then I could download The Public Domain and read it on my Kindle or any other ebook reader. My notes and highlights and bookmarks would follow, rather than being locked up, and I wouldn’t have to worry I’d lose either the book or my notes when I upgraded. I’d possess multiple copies which I could easily forward on to others, asking for their input. In other words, an advancement over a print book.

As it stands I can’t share a Kindle book, or a Kindle-ized book like The Public Domain. (Ironic, isn’t it, that this free book about free culture is now locked up on a proprietary device?) Turns out I don’t actually own my Kindle books. Evidently Amazon does. I just own the ability to view it. Basically I’ve given Amazon $400 for a book cover with a lock on it.

It doesn’t have to be this way, of course. Amazon could make the Kindle DRM-free and take a bold leap into the future, rather than these timid baby steps. The Kindle could be the open future of reading. If not, maybe some other device will. Maybe we’ll get lucky and Jeff Bezos will read The Public Domain and see the light.

The marginal cost=zero argument is common but we can’t take this too far. For example, unless a plane is completely full, the cost of adding me as a passenger is essentially zero. Is it really theft, therefore, if I simply sneak past the guards and enter the plane? Yet try to imagine the airlines thriving if everyone decides they’re the marginal passenger.

The fact that tens of thousands of people, some expert, others not-so-much, have created a unique and wonderful work in the Wikipedia doesn’t guarantee that similar work will, for example, create the next great American novel.

Indeed, the Internet has nothing to do with the issue of copying. It’s always been possible to copy books (a point frequently made on Teleread). If I were to re-typeset the Harry Potter books and offer them for sale in paper copies, this wouldn’t be any more (or less) theft than if I scanned it and offered it in digital form. Similarly, my applying labels identifying my books as being written, say, by Stephen King, Nora Roberts and J.K. Rowling don’t diminish the ability of those authors to continue to use their own names.

Ultimately, what we need is a balance. Waving hands and saying that some works may be created if we abandon copyright doesn’t address the issue of whether doing so will result in a better place. Certainly I believe it will not. My copyrighting my own works doesn’t interfere, after all, with anyone’s ability to put their own works in the public domain.

Rob Preece

Publisher, http://www.BooksForABuck.com

@Rob – Boyle definitely does *not* make the marginal cost=zero argument. In fact he supports what might best be called an evidence-based approach to copyright and repeatedly expresses his dismay that actual evidence is largely ignored in the copyright debates.

For example, he compares and contrasts the way that copyrights in databases are handled in the U.S. and Europe and admits he would have thought that creating a copyright in a specific database (for example, giving the publisher of a telephone book a copyright on the compilation of telephone data) would spur database development.

OTOH, the evidence is clear. The U.S. has no such copyright, while Europe has instituted once and the evidence is fairly clear that such a copyright does not encourage innovation. Of course, European regulators simply ignore their own reports showing exactly that . . . similar to the effectively unlimited copyrights in the United States that tie up pretty much everything forever in order to protect a few of the uber-popular properties (Boyle favors, if I recall correctly, requiring minimal cost copyright *renewals* so Disney can keep Mickey Mouse locked up forever while allowing orphan works to enter the public domain).

“Ultimately, what we need is a balance. Waving hands and saying that some works may be created if we abandon copyright doesn’t address the issue of whether doing so will result in a better place. Certainly I believe it will not. My copyrighting my own works doesn’t interfere, after all, with anyone’s ability to put their own works in the public domain.”

This is true but not the problem. If have a copy of book that was written in the 1940s and has been out of print since almost after it was published. The author is long dead and the publishing house long out of business. I’d love to make this book available on the Internet, but current copyright law makes it extremely expensive to determine who the current rights holder is to even approach that person or entities (and in some case ownership may literally be impossible to determine without very expensive legal investigation and possibly legal action).

Frankly, if intellectual property industries would just push for a reasonable solution to the orphan works problem instead of fighting such reform efforts at every turn, that would more than satisfy me.

Brian, I think Boyle doesn’t favor endless copyrights, but he would allow for easy-to-do renewals, for a certain period, for popular and lucrative copyrights, like Mickey Mouse. As I understand it, US law until 1978 allowed for a one-time 28-year copyright, renewable for a further 28 years. I’m not sure about after that; I don’t think Boyle mentions it specifically in the book. I agree, also, that that is not the primary issue: 95% of works are not commercially viable, and those should be set free. I guess I wouldn’t much mind, either, if the remaining 5% remained in proprietary hands.

Rob, as Brian says, Boyle is certainly not in favor of abandoning copyright. And the next great American novel will likely not be written in Wikipedia fashion (although who knows), but that doesn’t mean that it won’t be given away for free, under, say a Creative Commons license, as opposed to a traditional copyright. To take one instance among others: Cory Doctorow, who gives all his works away free online.

Thanks for the feedback and thoughts. Just a side note on the Cory Doctorow example–the man does make his money from selling books. He simply finds that giving away electronic versions of his books, at this time, gives him sufficient name recognition etc. that he sells enough paper books to make up for it. I suspect if I took one of Cory’s books and came out with a print version, his lawyers would be all over me in no time.

To make myself clear, I believe in the idea of a compromise between author rights and public domain. I personally think the Bono extensions went too far, that we’d be better off with something like 50 years or author’s life, whichever is longer. However, I’ll say from my standpoint that I wouldn’t spend the time I do acquiring, editing, paying artists, and promoting BooksForABuck.com original fiction if I didn’t have some assurance that big publishing companies couldn’t steal my work and offer them with no compensation to me or the author.

Rob Preece

Publisher, http://www.BooksForABuck.com

This is not an argument. It is a fact. Information is not the same as physical property. It never has been. It never will be. Anybody who claims differently is both lying to you and attempting to steal from you. The term “intellectual property” is just such a lie, and unfortunately, Mr. Boyle still uses this term liberally in his cellulose encased lecture.

In a nutshell, the problem is this: books contain speech recorded. If speech is Free as per the First Amendment, it cannot be restricted. Any restrictions on speech are harmful to society, like parceling out air and selling it would be. Would you deny people air in order to make a profit? Some things just cannot be private property.

@Rob: Your second post is entirely correct. Copyright should be limited entirely to sales. The author should get first cut of all monetary transactions involving his works — if there are any, but transactions not involving money should not be touched. That way, if money is to be made it will be the author that makes it, but people will not be compensating authors whose works nobody wants or tricking people into buying garbage books because they cannot sample the whole book before they buy.

Not completely true. They use their names as identifiers. If you nullify the identifying factor it certainly diminishes their ability to use their names in this fashion. However, they don’t have any natural right to use their names as identifiers, so the argument is moot.

OTOH, such identification helps both the public and the author (and most people think honesty is better than dishonesty anyway) so there is a lot to gain from having some law(s) against plagiarism, and there is very little to lose. Thus most people that are against copyright are also for various forms of antiplagiarism (e.g., trademarks).

Rob wrote,

“Thanks for the feedback and thoughts. Just a side note on the Cory Doctorow example–the man does make his money from selling books. He simply finds that giving away electronic versions of his books, at this time, gives him sufficient name recognition etc. that he sells enough paper books to make up for it. I suspect if I took one of Cory’s books and came out with a print version, his lawyers would be all over me in no time.”

I think what would be more interesting would be whether Cory D could release a novel under a pseudonym and find that releasing the CC version increases his psudonymic sales …i.e., is the sales that he and a handful of others report seeing from CC-ing their works largely a net-celeb effect that is not likely to be generalizable? We’ve seen posts on this blog related to folks who CC’d their novels and didn’t exactly see sales go through the roof (though one might argue that Cory is an especially gifted writer in his chosen genre).

And, of course, we still live in a world where most people want to read P-books even when electronic versions are (relatively) easily available. I read Cory’s “Down and Out” and “Eastern Standard Tribe” on a Windows Mobile PDA, but I suspect that puts me in the ranks of e-book enthusiasts rather than any general trend (I suspect *far* more people read those novels in p-book form than e-book form even though the e-book was free).

“As it stands I can’t share a Kindle book, or a Kindle-ized book like The Public Domain. (Ironic, isn’t it, that this free book about free culture is now locked up on a proprietary device?) Turns out I don’t actually own my Kindle books. Evidently Amazon does. I just own the ability to view it. Basically I’ve given Amazon $400 for a book cover with a lock on it.”

It’s not ironic. It’s sold on Amazon. Sounds logical to me. You want to share this book you bought with the planet and you can’t. If you want to share the book with me, first get to know me, then buy the paperback. I’ll give it back.

(PS. You buy a book about how to murder your wife and find it ironic that you can’t? Gee tough world we live in.)