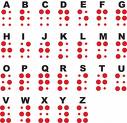

Back in January we did an article: “Listening to Braille” : Braille advocates at odds with new audio technologies. Now an article in CTV News, of Canada, discusses the same issue.

Back in January we did an article: “Listening to Braille” : Braille advocates at odds with new audio technologies. Now an article in CTV News, of Canada, discusses the same issue.

Less than 10 percent of Canada’s 830,000 vision impaired people can read braille. New technology, such as JAWS (Job Access With Speech) is gaining popularity and obviating the need for braille in many cases.

Nevertheless, the braille advocates are still there:

“What braille allows is for someone to gain literacy, to gain an understanding of sentence structure and grammar. Computer technology doesn’t replace how to learn to write, to spell, what punctuation is. Braille is that tool for literacy,” he says.

People with vision loss already face an unemployment rate of a staggering 70 per cent, Rafferty notes. That likelihood is worsened if a blind person doesn’t read braille. He says studies have shown that a visually impaired person who knows braille is much more likely to move to higher education and to become employed than someone who relies on voice synthesizers.

“Braille is critical for gaining knowledge of literacy and moving into successful employment. For anyone born blind or partially sighted as a youth, it provides them with a significant amount of additional learning,” says Rafferty.

The reporter’s “braille versus computer technology” slant is highly misleading. Electronic braille exists; in the U.S., the two main nonprofit providers of braille books, the Library of Congress and Bookshare.org, both offer electronic braille files as well as embossed (i.e. printed) braille books.

The problem with braille is not that it’s outdated; the problem is that it’s expensive. I could listen to a 250-page book for free through text-to-speech software, which is widely available as freeware and is packaged with many computer operating systems. There are even free screen readers for the blind now that will report all activities on the computer. But it would cost me $50 to buy that same book through Bookshare.org (and Bookshare.org’s prices are in no way above normal). If I wanted to read the book through electronic braille, the situation would be even worse. The cheapest electronic braille display (i.e. machine that shows electronic braille as raised dots) is, I believe, $1700. That’s a bargain; most braille displays are $5,000-10,000.

Imagine if, in order to read electronic text, you had to buy a $5,000 monitor. Computer literacy would sag.

Since only a very small percentage of published books have also been published as embossed braille books, the only way to keep braille alive will be to develop a way to make cheap braille displays. With that, a scanner, and an OCR system, blind readers will have access to virtually any book in the world in braille.

Technology developers have been promising cheaper braille displays for at least a decade (that being how long I’ve been partially sighted). I keep waiting for them to fulfill their promise.

we (society) need affordable electronic reading devices with a braille ‘display’. a flexible screen over a code-driven pinboard. (i’m not blind or low-vision, but i care about this.)

the problem with braille ‘hardcopy’, is that the raised dots get mooshed and become illegible over time. content is not *easily* available in hardcopy, either. those titles that may be had readily are for children, or religious in nature, or bestsellers. one can get other titles, but there’s no instant gratification. also, do you have any idea how huge braille books are? they are giant. no way could you even take ‘moby dick’ on your commute to work in a braille edition. if there were an affordable braille device that would refresh according to the same logic as an e-book, a blind or low-vision individual would have all of the same titles available to them as we have on our e-ink readers. it would take more engineering to figure out a way for the reading person to underline and annotate passages, but this would be essential functionality for learning. try *that* with an audiobook.

the same changes occur in the brain while a blind person is reading braille, as occur in the brain of a sighted person reading print. the activity builds synapses.

if i were to lose my eyesight i would make learning braille a priority, if for no other reason than to be able to listen to music while reading.

i’ve heard that this dream of mine is a reality — or something like it, anyway. i have not confirmed it. but if it is a reality, learning braille should be compulsory for the blind, just as learning to read print is compulsory for the rest of us.