Google Books isn’t just an e-book store. It’s a pile of data, waiting to be mined. And while the metadata on many of the books in Google’s database may not be in the best of shape, enough books have good metadata that they can be used for some fairly interesting projects.

Google Books isn’t just an e-book store. It’s a pile of data, waiting to be mined. And while the metadata on many of the books in Google’s database may not be in the best of shape, enough books have good metadata that they can be used for some fairly interesting projects.

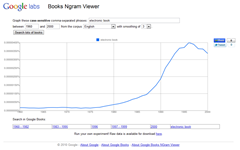

Ars Technica has the story on one of these. A group of Harvard researchers created a tool that could be used to trace the usage of words or phrases in books over the last few centuries. And what’s more, Google has made the tool publicly available via a web interface.

You can go to the site, type in words or phrases (several at a time, if you like) and trace their popularity over time and in comparison to each other. It’s a fascinating way to spend an hour or so.

The tool isn’t perfect—for one thing, it’s case-sensitive, and there’s no way to combine queries: I can see all uses of “Urban Fantasy” or “urban fantasy” on the same chart, but I can’t see a combination of the both terms into a single line. And also, it depends on the scan results from Google being reliable, which they are not always: when I query on “ebook” I get a number of erroneous results over the last few centuries including scan typos and, in some cases, Project Gutenberg e-books.

Following up a search on the “f word” brings to light another interesting shortcoming in Google’s optical character recognition. Investigating a peculiar set of peaks in its usage between about 1630 and 1810 brings search results that reveal Google has been translating the “long s” used in those days as a lower-case “f”, which leads to all sorts of amusing example sentences in the search results. (Update: Danny Sullivan of Search Engine Land discovered this, as well.)

And a search oddity that I get, in which a small number of uses are shown for 1900-1910 when I search on “cyberpunk” or “Geek Squad”, makes me wonder whether some of the metadata on their books is not as good as they think it is. (They don’t show up when I search Google Books on that time period, though.)

Still, it’s fairly interesting to look at the usage of words, including dirty ones, to see how often they have appeared in print over time. And further, it’s a great example of the kinds of uses that can come from having so much data together for the first time. With a little more refinement, this class of tool could be extremely valuable to scholarly research—as well as providing amusing ways for laypeople to pass the time.