It’s an interesting time to be watching the publishing industry and e-book sales. Two fairly well-regarded reports in the publishing industry have just come out, and taken together they offer some startling results. Have we reached a turning point, or a tipping point?

It’s an interesting time to be watching the publishing industry and e-book sales. Two fairly well-regarded reports in the publishing industry have just come out, and taken together they offer some startling results. Have we reached a turning point, or a tipping point?

The Association of American Publishers reports e-book sales fell by 10% in the first five months of the year. The New York Times, bastion of the traditional publishing industry, is busy Viewing With Alarm—or perhaps with relief that the publishing industry somehow Dodged A Bullet and print books aren’t dead after all. Perhaps this is where that analyst on Seeking Alpha who used it as proof that maybe Barnes & Noble isn’t doomed got the idea.

And yet, even the New York Times admits that it might not be seeing the whole picture, though it kind of buries this admission toward the very end of the article:

It is also possible that a growing number of people are still buying and reading e-books, just not from traditional publishers. The declining e-book sales reported by publishers do not account for the millions of readers who have migrated to cheap and plentiful self-published e-books, which often cost less than a dollar.

At Amazon, digital book sales have maintained their upward trajectory, according to Russell Grandinetti, senior vice president of Kindle. Last year, Amazon, which controls some 65 percent of the e-book market, introduced an e-book subscription service that allows readers to pay a flat monthly fee of $10 for unlimited digital reading. It offers more than a million titles, many of them from self-published authors.

On The Mad Genius Club, Cedar Sanderson is a bit less circumspect, when she links to an article explaining that data from the Association of American Publishers and Nielsen Bookscan have major holes. The funny thing, Sanderson notes, is that many of the books considered to have the most literary merit, such as nominees for the Man Booker Prize, tend to have the weakest sales.

Also less circumspect? The September 2015 Author Earnings report from last week, which bears the headline “AAP Reports Own Shrinking Market Share, Media Mistakes It for Flat US Ebook Market.” The AAP only covers 1,200 of the traditional publishers, Hugh Howey explains in the report, and Nielsen PubTrack only covers thirty of those publishers. Yet journalists report those figures as if they represented all of book sales.

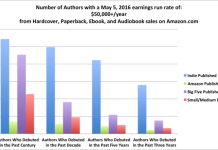

To be fair, up until a few years ago, they did represent all, or almost all, of book sales. But that was before Amazon threw open the self-publishing floodgates. And who tracks that Amazon flood? Author Earnings.

Here at AE, over the last seven quarters we have steadily built up a comprehensive database of quarterly cross-sectional snapshots of the Kindle store, each of which captures between 45% and 60% of Amazon’s daily ebook sales. And while Amazon’s Kindle store alone doesn’t comprise the entire US ebook market, it does account for 67% of all traditionally-published ebook sales by most accounts.

So we were in an ideal position to measure what percentage of the broader US ebook market the AAP’s 1200 reporting publishers truly account for. And far more importantly, we could measure how well the AAP’s widely publicized decline in ebook sales reflects the direction of the broader US ebook market over the last seven quarters.

Howey explains that, for this report, Author Earnings did some additional research on the books it had been tracking over the last seven reports (four from 2014 and three from 2015), checking each publisher to figure out which ones were tracked by AAP’s reports. The point of the exercise was to figure out what percentage of the Amazon sales Author Earnings analyzed were AAP books, non-AAP traditionally-published works, and indie works. And for the three most recent reports, they were able to segment indie works into those bearing an ISBN and those without, as well.

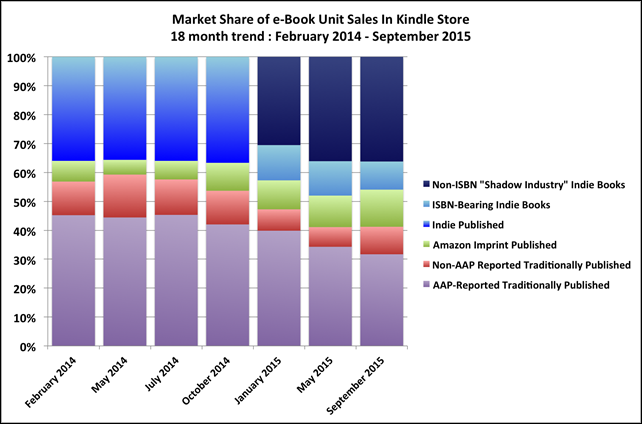

There were some interesting takeaways in the unit sales chart, such as the fact that traditionally-published e-books made up less than 55% of those e-books sold by Amazon in 2014. (45% were AAP-tracked; 10% were non-AAP-tracked.) The other 45% were Amazon imprints and self-published titles. And while Amazon’s statistics only accounted for 67% of e-book sales, the Author Earnings report that looked at Barnes & Noble instead of Amazon—where the lion’s share of that remaining 33% are—found similar numbers.

There were some interesting takeaways in the unit sales chart, such as the fact that traditionally-published e-books made up less than 55% of those e-books sold by Amazon in 2014. (45% were AAP-tracked; 10% were non-AAP-tracked.) The other 45% were Amazon imprints and self-published titles. And while Amazon’s statistics only accounted for 67% of e-book sales, the Author Earnings report that looked at Barnes & Noble instead of Amazon—where the lion’s share of that remaining 33% are—found similar numbers.

Author Earnings spends the next few sections going through the numbers for each of the market segments it splits the charts into, and finds some interesting things, but perhaps the most interesting in regard to the current e-book sales hysteria is that the AAP-tracked market share has fallen from 45% in 2014 to only 32% as of September 2015. Meanwhile, the market share of independent e-books without ISBNs, who aren’t tracked by any of the traditional industry data sources, has grown from 30% in January 2015 to 37% as of September.

To drive the point home, Howey notes:

When the AAP reports “declining ebook sales”, they are describing the shrinking portion of the US ebook market held by their 1200 participating traditional publishers, whose share of the broader US ebook market has fallen in the last 18 months from 46% of all Kindle ebook purchases to less than 32%.

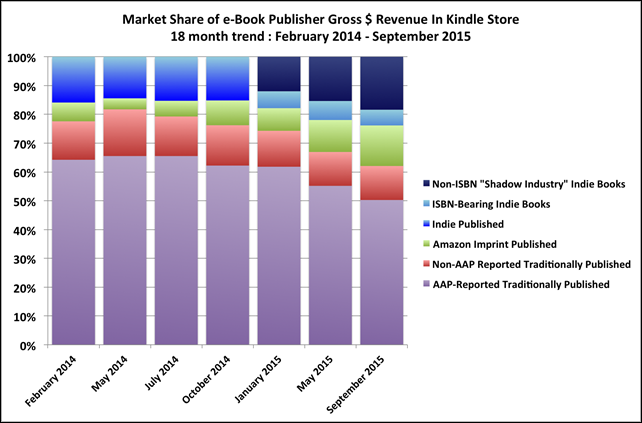

A sales revenue chart showed similar declines. Howey points to one of Mike Shatzkin’s blog posts positing that, until recently, the e-book market was growing so fast that the growth masked the decline in traditional-publisher revenue from falling sales due to agency pricing. (And some media outlets, such as the Wall Street Journal, have been taking notice—Google the headline to slip past the paywall.)

A sales revenue chart showed similar declines. Howey points to one of Mike Shatzkin’s blog posts positing that, until recently, the e-book market was growing so fast that the growth masked the decline in traditional-publisher revenue from falling sales due to agency pricing. (And some media outlets, such as the Wall Street Journal, have been taking notice—Google the headline to slip past the paywall.)

However, as that growth has slowed, it has allowed the decline to become more visible—but, Howey notes, even the slowed growth is still cushioning the actual impact of the losses, because Author Earnings’s charts show that traditional-publisher revenue is still falling more slowly than the actual market share of the publishers.

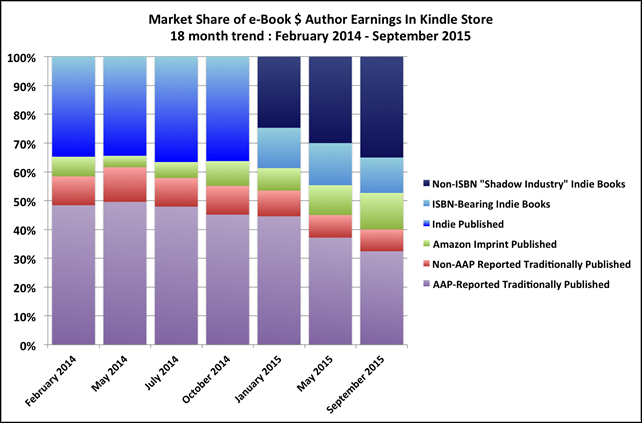

Switching to the chart of the titular author earnings from e-book sales, Howey notes that, over the last 18 months, the earnings split went from 60% traditional/40% self-publishing authors to precisely the other way around—as of September 2015, it’s now 60% self-publishing versus 40% traditional authors. He points out, “From an author-earnings perspective, in 18 short months, the US ebook market has flipped upside down.”

Switching to the chart of the titular author earnings from e-book sales, Howey notes that, over the last 18 months, the earnings split went from 60% traditional/40% self-publishing authors to precisely the other way around—as of September 2015, it’s now 60% self-publishing versus 40% traditional authors. He points out, “From an author-earnings perspective, in 18 short months, the US ebook market has flipped upside down.”

It is worth pointing out that even these numbers miss out on a large part of the overall book market—they reflect e-books, not print books, and as seen elsewhere (such as that New York Times article up at the top) print book sales are good and print bookstores are thriving. (Though it’s possible that part of the bump in print sales is because, due to agency pricing, many new-release hardcovers are actually the same price as or cheaper than the e-book version on Amazon.) But self-publishing is even making inroads into traditional print markets such as Wal-Mart.

The traditional publishing boat may have sprung a number of leaks, but it sounds like the publishers have only just noticed their shoes are soaked through. How long will they continue to believe that their declining e-book sales reflect the entire market? And how far will their sales decline before they notice that Amazon seems to be doing just fine on the strength of all the books that aren’t theirs? (Will they try to put the blame on Amazon for this again somehow?)

It’s going to be very interesting to watch the industry for signs of growing self-awareness over the next few months.

Update: I didn’t even notice this passage from that New York Times article until someone pointed it out in the discussion of that article on The Passive Voice:

Publishers, seeking to capitalize on the shift, are pouring money into their print infrastructures and distribution. Hachette added 218,000 square feet to its Indiana warehouse late last year, and Simon & Schuster is expanding its New Jersey distribution facility by 200,000 square feet.

Penguin Random House has invested nearly $100 million in expanding and updating its warehouses and speeding up distribution of its books. It added 365,000 square feet last year to its warehouse in Crawfordsville, Ind., more than doubling the size of the warehouse.

So not only are publishers basing their decisions on incomplete data, they’re doubling down by spending money to build out their warehouses in response to a “shift” that may not actually portend what they think it does. It’s going to be interesting indeed to watch this situation develop.

Really good article, Chris. Thanks for putting so much in one place.

As for this:

“It’s going to be very interesting to watch the industry for signs of growing self-awareness over the next few months.”…

I wouldn’t wait under water.