So, self-publishing and traditional-publishing author Hugh Howey published a report on some data he pulled from Amazon and crunched (Paul covered it here), purporting to show some things about the number of self-published books compared to those from traditional publishers. This has touched off a lot of blowback in the last couple of weeks as everyone and their uncle has attacked the data set for not being comprehensive.

So, self-publishing and traditional-publishing author Hugh Howey published a report on some data he pulled from Amazon and crunched (Paul covered it here), purporting to show some things about the number of self-published books compared to those from traditional publishers. This has touched off a lot of blowback in the last couple of weeks as everyone and their uncle has attacked the data set for not being comprehensive.

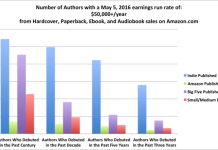

Howey has some interesting things to say, to be sure. Across 7,000 titles, Howey noticed that those from Big Five publishers tend to have the lowest average star rating, but the highest average price. He wondered if those two statistics might be related—that people’s amount of satisfaction relative to the amount they paid drives lower star ratings. He also noted that Big Five published titles made up only 28% of the titles on genre bestseller lists, and only 34% of daily genre unit sales (as estimated by sales rankings)—which is to say, the minority of the books sold. Furthermore, his data suggests e-books (in the form of Kindle books) made up 86% of the top 2500 and 92% of the top 100 selling titles from the genres.

Of course, the really controversial stuff comes when he totes up the daily revenue and estimates how much authors are making from their self-published works as opposed to how much they would make from pro-publishing. By his estimates, self-publishers are making the lion’s share of money from e-books on Amazon—nearly half of the daily total revenue—since they earn a bigger chunk from their sales than do those authors whose publishers take a big bite.

Howey was very up front that these figures represented a small bite of data from a single retailer, covering basically about a single day’s worth of Amazon sales. He didn’t claim that it was in any way conclusive, or that it was the last word in terms of what authors can earn by self-publishing. He even made the complete raw data set available for download, so people could crunch the numbers in whatever ways they preferred.

There were a lot of responses (Paul covers one here). From many of them, you would think Howey had advocated cooking and eating babies. Mike Shatzkin complained about Howey’s “agenda” (immediately drawing fire from J.A. Konrath). People (such as this blogger from Dear Author) complained that the figures weren’t complete, that he was making some very iffy guesses, and basically that this apple wasn’t, in fact, an orange, when Howey had never tried to claim it was. Writer and blogger Courtney Milan expressed skepticism because she couldn’t seem to get Howey’s numbers to match up for her own books.

Passive Guy, the blogger over at The Passive Voice, has been bemused by the large number of “overwrought” responses Howey’s post has engendered. Voices speaking for the publishing industry seem to be throwing tantrums:

Indie authors just can’t, can’t, can’t be selling more ebooks anywhere on Amazon than tradpub is. Indie bestsellers just can’t, can’t, can’t be making more money that tradpub authors are. They just can’t.

The vitriol and mathematical illiteracy have flowed like half-priced beer during Happy Hour.

Perhaps the greatest lesson to take away from all this is one that does not rely on the specific nuances of the numbers Howey crunched. It’s a more general realization, summed up by blogger J.W. Manus (found via the Passive Voice): no matter what the percentages are, it’s abundantly clear there are plenty of people making a go of self-publishing now, in ways that simply were not possible before e-books and especially the Kindle.

It used to be that (with just a few fortunate exceptions) the only way to get your book out there to a wide audience was to publish through a traditional publisher. When you did that, you didn’t have a lot of control over how it happened. The publishers controlled the vertical and the horizontal, and you took what crumbs they could give you and were grateful. But now there’s another way.

You had, of course, been able to self-publish through vanity presses for decades. (Donald Westlake poked fun at this to great effect in his 1968 novel God Save the Mark! in which one of the protagonist’s neighbors wanted to borrow money from him to vanity-publish his book about what the Roman wars would have been like if they had been fought with biplanes.) But you ended up having to hand-sell every copy of your book because the distribution for self-published titles wasn’t there. It just wasn’t worth it.

Then along comes Amazon and Smashwords and ebooks and something astonishing happens. Suddenly self-publishing is feasible. Hugh Howey’s Author Earnings data proves, without a doubt, that it is feasible. Self-publishing offers the means for any writer, anywhere, to find readers.

And that’s the real point.

Writers can find readers without the humiliations, the shitty contracts, the bad editorial, the lousy production values and high prices. They can do it without the condescending attitudes, disrespect and disregard. Writers can go with a publishing house if they want to. But if they don’t want to, they have the feasible option of self-publishing.

Judging by the sheer number of self-published works available to readers, a whole lot of writers don’t WANT to go with publishing houses.

Does it matter whether self-published author revenue makes up 30%, 40%, or 50% of daily revenue earned by authors from Amazon? Not really. All we need to know is that it’s a big, non-trivial chunk of revenue, no matter what the real size of the chunk actually is. Maybe Howey is off on the size of it in one direction or another, but there can be no question that it exists. And as he gets more data, the numbers should become more accurate.

Back when e-book self-publishing first started to hit it big, a lot of people were skeptical. It was just going to be a great big slushpile, where people who weren’t good enough to be published “professionally” would go. Nobody would be able to find anything decent to read in it. Nobody would make any money out of it. It was going to be a complete non-starter.

Well, it turns out that’s not the case. Sure, there’s plenty of drek. But there’s plenty of good stuff, too. And people don’t seem to be having trouble finding and buying it in large numbers. People don’t care who the publisher is, or even whether it has one. They care whether it looks good, whether it has good reviews, whether the sample they can read on Amazon is free of typos and errors, and possibly whether it’s from an author they’ve already read and enjoyed.

Sure, it’s not a magical kingdom where the streets are paved with gold. Not everyone is going to be able to make a living that way. Not everyone is even going to be able to make enough to buy a steak dinner that way. But putting your story out there and getting even a trickle of sales is better than sending it to a publisher and waiting months or years for a rejection…and then sending it to another one, lather, rinse, repeat. Even if the money isn’t great, a lot of writers would rather just know they’re being read.

As Howey points out in his report, you’ve got three possibilities for a manuscript: it’s bad, it’s good, or it’s great. Almost all of the bad and many of the good manuscripts will be rejected by publishers anyway, so better to get it out there and make some sales with it. Even a great manuscript will have a lengthy turnaround between being submitted and accepted, and being accepted and published. If your manuscript is great and you self-publish it (as Howey’s own self-published books evidently were), a traditional publisher will come to you, hat in hand, and you can decide then whether you want to go with them or not. In the meantime, you’re making a lot more per book sold than the publisher will give you, and getting paid more often too.

Small wonder that publishers are starting to feel threatened. What if everyone—or even just a whole bunch of people—decided they were no longer necessary? They can’t publish good books without decent manuscripts. Whether that’s actually likely to happen is not clear, but from all the vitriol coming out of publishing industry mouthpieces, it sounds like they’re certainly worried about it. (Howey has his own ideas about how publishers can fix things, but it’s not clear anyone is interested in listening.)

Update: Passive Guy over at The Passive Voice reblogged this post and added some cogent commentary of his own. He quite aptly points out that it wouldn’t take all writers leaving traditional publishers to trigger their collapse, just the bestselling ones. Because of publishing’s low margins, publishers rely on bestsellers like Harry Potter or Fifty Shades for profits year to year. If those start going to self-publishing…well. Small wonder they’re reacting so stridently to Howey’s figures.

Your comment: “It used to be that the only way to get your book out there to a wide audience was to publish through a traditional publisher.”

That is complete rubbish.

I started self-publishing in 1989. My books have sold over 800,000 copies since then. The books have been published in 22 languages in 29 countries. (My 111 foreign-rights deals were created and negotiated by me without the help of a North American foreign-rights agent.)

The role model who inspired me to self-publish my first three books was Robert J. Ringer. He is the only person to the best of my knowledge to write, self-publish, and market three #1 New York Times bestsellers in print editions.

Ringer’s first book, Winning Through Intimidation, was published in 1973. After the manuscript was rejected by 10 major publishers, Ringer chose to self-publish.

“Winning Through Intimidation” became a true bestseller, spending 36 weeks at

the top of the “The New York Times” Best Seller list. Ringer self-published his second book in 1978. “Looking Out for Number One” was also a New York Times bestseller as was “Restoring the American Dream”, which was published in 1979.

Not so long ago the first two of Ringer’s self-published books were listed by “The New York Times” among the 15 best-selling motivational books of all time. Keep in mind that Ringer was generating sales in the millions of his self-published books in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

In short, there has never been a time that the only way you could get your book out to a wide audience was through a traditional publisher. Robert J. Ringer could get his self-published books out to a wide audience in the 1970’s and 1980’s. I did it in the 1990’s, 2000’s, and continue to do it today. I can still do it with a new print book (forgetting about ebooks if I want) whenever I choose to. All it takes is being a 1-percenter in regards to creativity, critical thinking, common sense, and motivation.

Ernie J. Zelinski

The Prosperity Guy

“Helping Adventurous Souls Live Prosperous and Free”

Author of the Bestseller “How to Retire Happy, Wild, and Free”

(Over 200,000 copies sold and published in 9 languages)

and the International Bestseller “The Joy of Not Working’

(Over 250,000 copies sold and published in 17 languages)

I wouldn’t say two anecdotal exceptions necessarily make it “complete rubbish.” There are exceptions to every rule, and those few lucky and hard-working people who were able to self-publish and get their works to a broader audience were definitely the exception in those days. Now, they’re the rule.

So nice to see a reasoned response to Howey’s report. The abject dismissals I’ve seen are nothing short of an ostrich shoving his head in the sand.

The numbers that the big publishers want everyone to ignore are the gigantic portions of profit they are making from ebooks — and the pittance their authors earn on those same books. Right there is the reason the trad pubs had a banner year last year.

quote from article: “Howey noticed that those from Big Five publishers tend to have the lowest average star rating, but the highest average price. He wondered if those two statistics might be related—that people’s amount of satisfaction relative to the amount they paid drives lower star ratings.”

Hugh Howey is making an assumption based on online customer reviews without acknowledging or apparently being aware of how much coverage and research there has been, and is, about how gamed online customer reviews are. Has he been living in a cave or does he have some other reason to suggest that online customer reviews are credible?

Jim: Funny thing about that. The Harvard Business Review has done a study that suggests that, by and large, Amazon customer reviews are just as accurate as professional reviews.

Excellent summary, Chris! Thanks.

–Mark