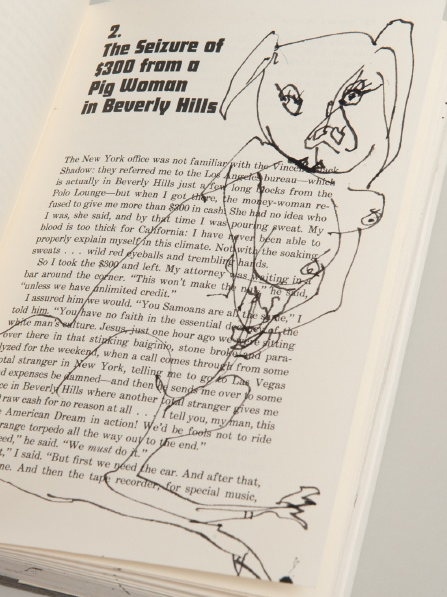

British book bloggers and tweeters are enthusing over the ‘First Editions, Second Thoughts‘ auction at Sotheby’s of print first editions annotated by their authors, including JK Rowling, Hilary Mantel, Philip Pullman, Nick Hornby and Ian McEwan, to be sold off in aid of English PEN. The Guardian has put together a beautiful clickable interactive gallery of the sale.

British book bloggers and tweeters are enthusing over the ‘First Editions, Second Thoughts‘ auction at Sotheby’s of print first editions annotated by their authors, including JK Rowling, Hilary Mantel, Philip Pullman, Nick Hornby and Ian McEwan, to be sold off in aid of English PEN. The Guardian has put together a beautiful clickable interactive gallery of the sale.

Rowling’s marks on a first edition copy of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Sorcerer’s Stone in the U.S.) include hilarious insight into the genesis of Quidditch, which, her annotation states, “was invented in a small hotel in Manchester after a row with my then boyfriend. I had been pondering the things that hold a society together, cause it to congregate and signify its particular character and knew I needed a sport. It infuriates men, in my experience (why is the Snitch so valuable etc.), which is quite satisfying given my state of mind when I invented it.” Ian Rankin writes next to the publisher’s logo of Knots and Crosses, “One of six publishers the book was sent to; the other five turned it down.” Nick Hornby says in the endpaper of Fever Pitch, “Dear reader, How different this book would be if I were to write it now! Except of course, I couldn’t write it now, I’m too old.”

Obviously, such sales may be rarer in future. Although the documents above underline the perennial importance of the editing, reviewing and redaction process, I find it hard to imagine collectors paying for a great author’s Commented PDF file or Track Changes-enabled Word document. It could happen: It just feels intuitively less likely. (They might pay for the device that said author used to write those files, though. And remember, these are marks after the fact, not on work in progress.

Obviously, such sales may be rarer in future. Although the documents above underline the perennial importance of the editing, reviewing and redaction process, I find it hard to imagine collectors paying for a great author’s Commented PDF file or Track Changes-enabled Word document. It could happen: It just feels intuitively less likely. (They might pay for the device that said author used to write those files, though. And remember, these are marks after the fact, not on work in progress.

Don’t assume there will be no marked-up proofs and hard copies at all in future, though. David Gaughran, in his industry standard self-publishing self-help guide Let’s Get Digital, recommends writers to submit to the discipline of printing out work to read it through on paper, no matter how wedded to digital they are. “You will be surprised at how many more errors you spot on a printed page compared to on-screen,” he affirms. Whether technology like Sony’s new 13-inch display makes a difference to that remains to be seen.

Furthermore, writers are as individual and particular as cats when it comes to how they write and what they write with. Some churn out copy with mechanic zeal, others elevate the creative process to a near-mystic ritual with its own instruments and totems. Come what may, some are going to stick to working on paper, longhand. (I cheat by using HWR onscreen, but I still can’t get away from that nagging feeling that prose ground out on a keyboard lacks the work and concentration, the pause for reflection, needed to be truly lasting.)

But when John Banville remarks in his copy of The Sea, “Nice typographical accident, this sudden top of the page. It still shocks, I think,” of course he’s picking up something that could be changed in a moment in a digital version. With digital, second thoughts don’t have to wait on a second edition.