I finished reading Fred Vogelstein’s book Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution, which I mentioned in my post yesterday. I quite enjoyed it. Even though I read the news reports of the events it describes as they happened, you don’t get the big picture until you read a book like this, that looks back and puts everything together in the proper context.

I finished reading Fred Vogelstein’s book Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution, which I mentioned in my post yesterday. I quite enjoyed it. Even though I read the news reports of the events it describes as they happened, you don’t get the big picture until you read a book like this, that looks back and puts everything together in the proper context.

The book covers the development of the iPhone and Android phones, touches on the iPad and what it meant, goes over the Apple vs. Samsung patent lawsuit, and then wraps up by looking at how these gadgets have changed the world up to the present day.

You could look at this book as the ideal companion piece to The Battle of $9.99: How Apple, Amazon, and the Big Six Publishers Changed the E-Book Business Overnight. It fills in a great deal of context and shows how Apple got to the point where it felt it needed to kneecap Amazon to enter the e-book business itself—but doesn’t actually go there, which is why you need to read The Battle of $9.99. Dogfight barely mentions the iBooks store, just touching on the three-month period Eddy Cue was given to develop it in the run-up to the iPad launch and at one point quoting from his testimony in the anti-trust trial. Not too surprising, I guess, since that really fell outside the scope of this story.

One curious omission is that it discusses the development of iOS and Android phones, and the iPad, but doesn’t say anything about how Android made the jump to tablets, or the wide variety of Android tablets there are (including the ones that OEMs lock down and customize, such as the Kindle and the Nook). It mentions the iPad Mini, but doesn’t mention that this was a direct response to the popularity of 7” Android tablets. Kind of a pity, really. I was hoping to hear in more detail about why most devices skip over Android 3 and go right from 2.3 to 4.0. It feels like I got the beginning of the Android story, then it jumped to the epilogue. I suppose there was only so much Vogelstein could cover so he just hit the high points.

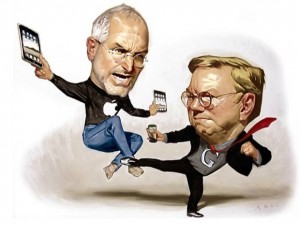

In some ways it reads like a Greek tragedy. In the beginning, Sergei Brin and Larry Page respected and looked up to Steve Jobs. When they were pressed to take on a more experienced CEO to guide their young company, at one point they said the only CEO they would accept would be Jobs. Since he wasn’t exactly going to leave his job at Apple, this was rather unlikely, but he was flattered enough to befriend them and serve as a sort of mentor. But over time, the relationship would fall apart, leaving an embittered, dying Jobs swearing to his biographer that he would spend every penny he had and fight to his last breath to take Android down.

In some ways it reads like a Greek tragedy. In the beginning, Sergei Brin and Larry Page respected and looked up to Steve Jobs. When they were pressed to take on a more experienced CEO to guide their young company, at one point they said the only CEO they would accept would be Jobs. Since he wasn’t exactly going to leave his job at Apple, this was rather unlikely, but he was flattered enough to befriend them and serve as a sort of mentor. But over time, the relationship would fall apart, leaving an embittered, dying Jobs swearing to his biographer that he would spend every penny he had and fight to his last breath to take Android down.

As I mentioned in the piece yesterday, before Apple and Google came along, the cell phone field was a mare’s nest of dozens of incompatible devices, each with its own different requirements for software. Apple initially didn’t want to get into cell phones at all, but was worried that, as carriers came out with their own “music phones,” they could steal the momentum away from the iPod. The iPod was still in its first year or two of release, and it wasn’t yet clear that it was going to be the breakout hit it became in later years. Meanwhile, Google, who made its revenue from search, was experiencing frustration trying to finagle its search app into the zillions of extant phones. And they were both worried about Microsoft figuring out a way to dominate mobile as well as the desktop.

Apart from cooperating with Motorola on the unimpressive ROKR phone, Apple originally didn’t want to have to deal with the carriers at all, but was gradually worn down by a Cingular negotiator and a number of Apple executives.

“We were spending all this time putting iPod features in Motorola phones. That just seemed ass-backwards to me,” said [Apple exec Steve] Bell, who now is cohead of Intel’s mobile-device effort. He told Jobs that the cell phone itself was on the verge of becoming the most important consumer electronics device of all time, that no one was good at making them, and that, therefore, “if we [Apple] just took the iPod-user experience and some of the other stuff we were working on, we could own the market.”

So they determined to take some designs that designer Jony Ive had for future iPods and make a phone out of them.

Meanwhile, Andy Rubin, CEO of the company “Danger” that produced the Sidekick/Hiptop line of mobile phones (our founder David Rothman took note of it back in 2002), was looking for backing for his Android project to create a mobile phone operating system—which he also saw as the future of consumer electronics technology. As it happened, Larry Page loved the Sidekick, in part because it was the only mobile phone to offer a full-featured web browsing experience at the time. And Google, fed up with trying to make its apps work on everybody else’s phones, was looking to do something similar—so Page decided just to buy Android outright and put Rubin’s team to work on it.

The story of both teams was fraught with strife. On the Apple side, conflicts between the chiefs of the hardware and software divisions responsible for the iPhone often had Steve Jobs have to end up mediating when meetings turned into shouting matches. On the Google side, the conflict was between Rubin’s team, which was kept insulated from the rest of Google in a manner at odds with Google’s corporate culture, and the rest of the corporate culture—notably the division responsible for developing apps for the iPhone, led by ex-Microsoft exec Vic Gundotra.

When the iPhone launched, as the excerpt I linked yesterday showed, it all but poleaxed the Android team. And then when it was actually released, it went on to be successful beyond anybody’s wildest dreams in spite of the original model’s omissions and flaws.

It wasn’t just that the iPhone had a new kind of touchscreen, or ran the most sophisticated software ever put in a phone, or had an Internet browser that wasn’t crippled, or had voice mail that could be listened to in any order, or ran Google Maps and YouTube, or was a music and movie player and a camera. It’s that it appeared to do all those things well and beautifully at the same time. Strangers would accost you in places and ask if they could touch it— as if you had just bought the most beautiful sports car in the world. Its touchscreen worked so well that devices long taken for granted as integral parts of the computing experience— the mouse, the trackpad, and the stylus— suddenly seemed like kluges. They seemed like bad substitutes for what we should have been able to do all along— point and click with our digits instead of a mechanical substitute. All of this captivated not just consumers but investors. A year after Jobs had unveiled the iPhone, Apple’s stock price had doubled.

Then the conflicts broke out company to company after Google first demonstrated its fledgling Android operating system. A livid Steve Jobs demanded Google remove multitouch features or Apple would sue. Google acquiesced, and its first model was nothing to write home about. But paradoxically, this served to draw the carriers apart from AT&T (who had bought Cingular, and hence were Apple’s exclusive carrier partner until 2011) together behind Google, because they saw potential in the operating system and needed something that could compete with the AT&T-only iPhone.

The Apple and Google partnership continued to unravel. Google submitted an app for its new Google Voice service to Apple; Apple rejected it (it was, after all, basically a Trojan horse, that cut the iPhone’s core phone functionality out and handed it over to Google), the FCC looked into it, and Apple ended up backing down and allowing it into the store. Apple attempted to come up with replacements for the apps Google had previously provided, switching Siri over to using Bing and creating a replacement Maps app that was such a fiasco that it led to the original software chief for the iPhone leaving apple. Google added multitouch back into subsequent Android operating system revisions. And Apple started suing Android phone makers, including Samsung. (Apple later won a $1 billion judgment against Samsung. The book doesn’t delve into or even mention the irregularities in that verdict, however.)

The other revolutionary device Apple created was the iPad. Its roots actually hark back before the iPhone, born of Steve Jobs’s irritation with a Microsoft employee spouting off about the tablets they were working on at a party in 2002. The problem was that the technology to make a useful tablet just didn’t exist yet, and they had to shelve the plans until it did.

The iPad debuted to less than overwhelming reaction at the launch event, but once people were actually able to get their hands on it they soon realized exactly why they needed it. Lighter than a laptop, it nonetheless did most of the things people needed laptops for very well, and in a much smaller form factor.

The upshot of all this is, smartphones and tablets have revolutionized and disrupted pretty much all major content-related fields.

The iPod and iTunes changed the way people bought and listened to music. The iPhone changed what people could expect from their cell phones. But the iPad was turning five industries upside down. It was changing the way consumers bought and read books, newspapers, and magazines. And it was changing the way they watched movies and television. Revenues from these businesses totaled about $ 250 billion, or about 2 percent of the GDP.

In the early days of the Internet, companies invested in computer-on-TV devices, assuming that when convergence came, everything would converge through the TV set. They invariably flopped. But now that we have small screens we can always carry with us, with processors good enough and Internet fast enough to stream video in real time, more and more people are choosing to watch TV on those screens, via services like Netflix and Hulu or even disruptive startups like the legally-embattled Aereo. Cable television isn’t viewed as necessary anymore, with these other programming sources available. Streaming services are funding their own TV series, such as Netflix’s House of Cards.

Vogelstein closes with an anecdote about how Larry Page unexpectedly took the podium at a keynote presentation to speak about his vision for the future. Page said:

You take out your phone, and you hold it out, it’s almost as big as the TV or a screen you’re looking at. It has the same resolution as well. And so if you’re nearsighted, a smartphone and a big display are kind of the same thing now. Which is amazing. Absolutely amazing … We haven’t seen this rate of change in computing for a long time—probably not since the birth of the personal computer. But when I think about it, I think we’re all here because we share a deep sense of optimism about the potential of technology to improve people’s lives, and the world, as part of that.

By comparison, Apple’s CEO Tim Cook, when asked what he saw for the future, replied, “We believe in the element of surprise.”

In the end, I quite enjoyed Dogfight, even with its curious omissions. It gave me a clearer picture of what went into the phone and tablet gizmos I carry around, and a new appreciation for just how miraculous those little devices are. Who knows what lies ahead? Will Google Glass and the imitators it spawns be the next frontier of mobile computing, or just an interesting curiosity? It should be fun finding out.

The more curious thing to me was the part of the story where Google realized that they would have to scrap their smart phone work and start over because the iPhone so changed the smart phone game. According to this account, this epiphany didn’t occur until the Steve Jobs iPhone announcement. Other accounts suggest that it happened much earlier and at the hands of Eric Schmidt who sat on Apple’s board from 2006 until 2009.

I am reminded that Napoleon is supposed to have said that, “history is a lie – agreed upon.”

Perhaps the players in this drama are trying to shape the story that most of us agree upon.