A recent article by Claire Shaw in the UK Guardian Higher Education Network purports to lay bare how “University libraries are shaping the future of learning and research.” And although the article doesn’t claim at any level deeper than the subtitle that libraries are actually dictating how we learn, rather than vice versa, it does demonstrate how ebooks, e-learning and related developments are causing academic libraries to mutate into new forms.

It stands to reason that university libraries are going to be at the sharp end of the debate on what all libraries are for in the ebook era, when the internet itself in theory forms the ultimate library, surrounding us all like Borges’s Library of Babel. If any physical libraries are mission-critical to the needs of their supporting communities, they are. And although Shaw’s article is written very close to the architectural perspective, it stays focused on how a library is used as the prime determinant of university library design.

“Pedagogy is the driver for the changes in library design,” Ann Rossiter, director of the Society of College, National and University Libraries, says in the article: “changes to the way undergraduates are expected to study, for example, including more social spaces, more social learning and group learning.”

Utilitarian considerations of functionality can also have an aesthetic and psychological component, though. It’s hard to imagine a server farm ever having the power of the Biblioteca Marciana, but a reading room of flickering screens might have a spectral beauty to it, more like the inside of a planetarium. Shaw cites Les Watson, former pro vice-chancellor at Glasgow Caledonian University, on the potential practical impact : “It is clear to me that the spaces in which we work and learn have both psychological and emotional impacts on use and also that learning is affected by our emotions and psyche so it seems feasible that better space can enhance learning performance. But there is no real evidence about what works and why so far.”

As someone who suffered with the shoddily compromised design of the Seeley Historical Library at the University of Cambridge, I know what he means. But for better or worse, he also means more than just pleasant buildings. The hidden agenda is what Watson refers to “in the era of annual national student satisfaction surveys” – good design as a competitive edge in student recruitment. Diane Job, director of library services at the University of Birmingham, also hints at this when Shaw quotes her as saying: “Our fundamental principle is putting people at the heart of the library – whereas libraries from a bygone age put the collections as the most important thing.”

It is university libraries being driven by undergraduate needs, as temples of learning and instruction, but not of enquiry and research: graduate fabs, extensions of the lecture room. That certainly reflects where the power and the money is now in academia. Perhaps it’s also a more insidious element in the digitally-focused shift towards information technology and learning in the cloud; rather than a loss of faith in books, a loss of faith in ideas and the intellectual inquiry of the individual mind. It’s hard to imagine the next Marx or Einstein coming out of a scale of priorities like that.

University libraries, such as the ones I frequent here in the US, have experienced a sharp decline in the presence of students. Assignments are more easily cobbled together with a little help from friends like Google than trekking through the stacks as I did in my student days. That makes it harder to justify the costs of these spaces and continuing acquisitions. So no wonder there is an effort underway to bring more students into the library. Facilitating group work is certainly valuable but there is much more that libraries can do to remain viable in the digital era. Helping students figure out what to look for, how to find it and, most importantly, how to evaluate what they find and use it without committing plagiarism are at the top of my list. Finally, as we move toward most everything being in digital form, we have to question why every academic library has to have a copy of the same work.

So, yes, academic libraries really need to reinvent themselves.

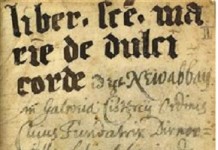

I certainly agree with Frank. To add to his remarks I would offer that one of the resources not held in common by research libraries are their own imaging and reformatting projects especially those applied to non-book formats. These resources are, of course, shared, but their “publishing” and the teaching agendas are locally hosted and preserved as unique collection types. There is also an underlying role of “on-site” resources presented by special collections within research libraries.

So the age of library collections is not yet over and the age of librarian mediation across formats and collections has never been interrupted.

I ran across “25 Ways to Reduce the Cost of College: #18 Digitize Academic Libraries” shortly after reading this so thought it might be of interest. Here it is: http://www.centerforcollegeaffordability.org/uploads/25_Ways_Ch18.pdf

Frank, I have never heard of that group, but I can tell you that they are completely wrong in that statement you linked to. Academic libraries are moving online because they have to, but it is vastly more expensive to subscribe to a journal online than in print. They are saving money by cutting subscriptions, even though they don’t want to, since they are losing funding as well. Most items in a library collection are under copyright, or might be under copyright, so any digitization project would further increase costs for the library. The library would have to fund the search for copyright owners, fund people to do the actual scanning, and fund the presentation of material. Regarding libraries, there are few suggestions someone could make to increase library costs more than that one.