After obliquely addressing the matter in his last few posts about whether American publishers can get in on the European English-language e-book market, publishing consultant Mike Shatzkin’s latest blog post takes a direct look at the problems of territorial restrictions in e-books.

After obliquely addressing the matter in his last few posts about whether American publishers can get in on the European English-language e-book market, publishing consultant Mike Shatzkin’s latest blog post takes a direct look at the problems of territorial restrictions in e-books.

He begins by drawing parallels to the differences in American and British Beatles albums in the sixties (the American editions left songs off of each one) and his inability to watch American football games in Europe now despite the technology being readily available. Similarly, though there is nothing technically preventing e-books from being downloaded anywhere in the world, contractual restrictions currently get in the way.

Shatzkin, interestingly enough, places a lot of the blame on agency pricing.

In the past several months, readers of this blog from around the world have commented on the unavailability of ebook titles in their territories even though publishers would have the right to sell them. As near as we can tell, this problem often tracks back to big publishers that have gone to agency pricing. (That’s where the publisher sets the price to the end consumer and becomes the seller-of-record rather than the retailer intermediary being the seller.) It would appear that many (if not all) agency publishers have withheld their titles in territories outside the United States, even if they would have the rights to sell in those territories.

I’m certainly not going to object to placing more blame for consumer aggravation on agency pricing, but as I pointed out in a follow-up comment, geographical restrictions went into effect at e-book sellers such as eReader and Fictionwise in April, 2009—almost a whole year before agency pricing kicked in, and certainly a number of months before anyone even proposed it as an idea.

It’s hard to imagine an inability to implement agency pricing being the cause for these restrictions so long before anyone even knew what it was. Charlie Stross’s explanation that agents often withhold regional rights because they can make more money for the author by selling them off piecemeal makes more sense—though Shatzkin is talking about a refusal to sell even in areas where the publisher does hold the rights.

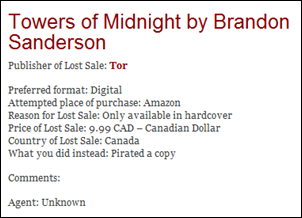

Shatzkin also notes hearing via a site set up by Jane Litte to track lost book sales that though Amazon.com sells globally, Amazon.co.uk only sells to the UK. “So if the rights to, let’s say Switzerland, are owned by the UK publisher, that publisher would have to have the ebook available through the US branch of Amazon or it wouldn’t be available to the Amazon customer in Switzerland!”

He seems to be referring mainly to e-books here, which is a bit odd, since I know that Amazon.com specifically does not sell big-six publisher e-books world-wide in any event for the same reason that Fictionwise and eReader don’t. Indeed, it caused a minor controversy a couple of weeks ago when The Bookseller pointed out how easy it was to bypass those territorial restrictions.

I do know that this is not true for print books and other physical media. I’ve ordered a couple of Region 2 DVD titles from amazon.de and amazon.fr, and they certainly shipped them to me. The fact that Amazon uses the same interface and customer database for all of its sites worldwide, just in different languages, has long meant that people who are determined to order products from overseas stores can just fill out their American Amazon shipping information, then log in with their username and password at the overseas site and order the books they want by pressing the right buttons even if they don’t know the language.

To make sure this was still the case, I just now went to Amazon.co.uk and set up a test order for some Harry Potter books. Not only were they perfectly willing to charge a credit card with a US address to ship the books to a US address, they even had a currency converter to let me know how much the order would come to in US dollars. (This only seems to hold true for some items, though. When I wanted to order some British Doctor Who toys a few years back, I had to wait until my brother was visiting Europe and get them shipped to his hotel room for pickup; Amazon wouldn’t ship them overseas.)

To make sure this was still the case, I just now went to Amazon.co.uk and set up a test order for some Harry Potter books. Not only were they perfectly willing to charge a credit card with a US address to ship the books to a US address, they even had a currency converter to let me know how much the order would come to in US dollars. (This only seems to hold true for some items, though. When I wanted to order some British Doctor Who toys a few years back, I had to wait until my brother was visiting Europe and get them shipped to his hotel room for pickup; Amazon wouldn’t ship them overseas.)

For that matter, the whole reason that we got global simultaneous-release Harry Potter midnight launch parties starting with the third book was that the publishers noticed Americans were ordering a lot of copies of the British editions of the Harry Potter books from Amazon in the UK in the couple-of-months window between their UK and US availability. As I just proved, it’s still possible to order the UK versions of the Harry Potter books from America (just in case you prefer seeing the British spellings and use of terms like “philosopher’s stone” rather than “sorcerer’s stone”)—something you can’t do with e-books as it now stands.

Although he talked earlier about agency pricing preventing e-book publication in areas where publishers do hold rights but do not have agency pricing yet, Shatzkin moves on to address the issue of publishers not having rights in some regions at all.

One publisher on the list [of lost book sales on Jane Litte’s site] immediately looked up the complaints against his house, which the web site makes very easy to do. Among the first books he saw was one where his company had US rights only. The complaint was from a person who couldn’t get the book in a territory controlled by the UK publisher. Yet the US publisher was listed as the “culprit” failing to make the book available.

Even if books do find publishers who can buy and make use of global rather than territorial rights, Shatzkin notes, a lack of agency pricing in all areas may still hold back publishers from publishing their books there. The problem is a conflict between the old scarcity-based rules of the old print publishing world and the new possibilities inherent in the e-book.

Just about the first rule any agent or publisher engaged in rights dealing learns is “acquire rights broadly, license rights narrowly.” Any agent who is a competent professional holds back any rights they can in any deal they make. And most agents trying to maximize an author’s English-language revenue starts with the assumption that they accomplish that by making separate deals in New York and London. Those deals are still primarily about print books. Ebook rights and various other territories, like Europe, are still pawns in the bigger game.

Shatzkin thinks that we’ll get global e-books sooner or later, but it will take a number of years for business realities to catch up to technological ones. But the legal barriers caused by rights issues will be easier to overcome than logistical issues posed by printed matter—especially as agents and authors start to realize that they are aggravating the people who want to be their paying customers. He writes that he would not be surprised if sooner or later future deals require publishers to make e-books available everywhere they hold distribution rights, because the authors who are agents’ clients will demand it.

Nowhere in the article does Shatzkin directly mention piracy, though he does point out that, to book consumers, the territorial rights issues “appear to be nonsensical barriers [that] block them from purchasing and consuming content that technology could easily deliver to them and for which they’d be happy to pay a fair price.” But a number of the entries on Litte’s site state that when consumers could not buy the e-book they wanted, they pirated it instead.

Nowhere in the article does Shatzkin directly mention piracy, though he does point out that, to book consumers, the territorial rights issues “appear to be nonsensical barriers [that] block them from purchasing and consuming content that technology could easily deliver to them and for which they’d be happy to pay a fair price.” But a number of the entries on Litte’s site state that when consumers could not buy the e-book they wanted, they pirated it instead.

Publishers had better start paying attention to this issue soon, or they risk losing a lot of sales. And as badly as the print publishing industry is struggling at this point, you’d think they’d be more concerned about that.

It needs to be noted that in some instances, especially as regards Canada, the geographic restrictions are (at least in part) a function of national laws. Some countries still seem to think that they’re sovereign and not part of the United States of Internet. 🙂

Canada’s Investment Canada Act protects Canadian authors, publishers, distributors, and booksellers against competition from non-Canadians (read: Americans). It also protects Canadian culture against books containing non-Canadian words like “center” and “color”. Apple’s Canadian version of the iBookstore is currently being investigated under the Investment Canada Act. Apple should’ve taken a cue from Amazon, who found that if you dump $20 million into the correct pockets you can get an exemption from the Honourable James Moore, Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages.

NAFTA and its predecessor, the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement, have special exemptions to not cover cultural items such as books.

Many other countries don’t have quite the enthusiasm for Freedom of the Press that the US does. For example, Salman Rushdie’s “Satanic Verses” is not welcome in many parts of the world. China is reportedly rather finicky about what kind of outside culture makes its way into the country.

Doug, it’s true that Canada has cultural protection laws and I’m sure other countries do as well. Unlike Canada some of the other countries can probably define the culture they are trying to protect. ;^) As a Canadian citizen I think the cultural protection laws are irrelevant in the internet age and I don’t believe that a Canadian based publisher (that is only interested in profit) has any more interest in protecting Canada’s culture then a profit centric publisher based elsewhere.

It’s not the Canadian government that has stopped me from buying e-books from Fictionwise.

@Bow W

here here. my sentiments exactly. who’s protecting who and from what?

let me read what i want to read. and let me buy what i want to read.

or else, how are we different from other so-called less democratic countries.

i mean really …