What do you call a writer who insists that she “[does] not mind used bookstores” and then spends the rest of a fairly long essay inveigling against them? You might call her Kristen Lamb, because that happens to be her name.

What do you call a writer who insists that she “[does] not mind used bookstores” and then spends the rest of a fairly long essay inveigling against them? You might call her Kristen Lamb, because that happens to be her name.

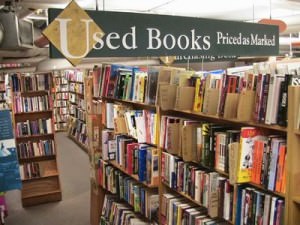

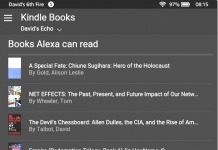

In a post to her blog, Lamb complains about that Washington Post article I covered a while ago, about used-book stores making a comeback. She is puzzled that she sees so many writers reacting to this article as if it’s good news, when in fact writers don’t actually make any money when someone buys one of their books second-hand—and for all that a lot of publishers consider Amazon and e-books to be the devil, at least e-books do earn the writer money. She is concerned that many readers may not know this fact, and thinks writers should do their part to educate them.

Lamb clarifies in comments, and in the comments where the article is discussed on The Passive Voice, that she’s not arguing against used bookstores, per se, but trying to tell writers they should stop promoting them because they’re cutting their own throat. But when she actually directly compares used bookstores to piracy, because both broaden the author’s exposure without paying him, it becomes a little harder to take her seriously. (Even when she subsequently adds that she knows used bookstores are “not actually stealing.” The timbre of the blog post seems to be that it’s all right to tear down used bookstores as much as she wants as long as she says first or afterward that she doesn’t really mean it.)

The fact that used bookstores don’t pay royalties has been a concern for some time. In 2008, a group wanted to amend copyright law to require used bookstores to pay royalties on recently-published books when resold used. And even then, a number of authors went to bat for used-book stores, even though they knew used books didn’t pay them directly.

From a practical standpoint, for me and us, when one publisher gave up on us, it was the used bookstores that hand-sold our used books and kept us in front of readers, and when we went to conventions we autographed thousands of used books … for readers who wanted more. So, we support used bookstores, we sign used books at conventions, bookstores, and fleamarkets. Readers deserve the opportunity, especially in these times when jobs and cash are at a premium, to buy a used book. Yes we need to sell new books, too,but used book dealers are not taking food out of our pockets.

And Eric Flint wrote:

What I like to see are copies of my books available all over the place in editions that bring me no direct income—whether that’s in a library, a used bookstore, a remaindered table, or simply being passed from one person to another. Because I know that that “spillage” is simply the necessary lubricant for this very opaque market that my livelihood depends upon. It’s that spillage—that penumbra of free or cheap copies, if you will—that makes everything else possible in the first place.

What I don’t want to see are those books piling up, because they aren’t moving. (Or the library equivalent, which is not being checked out.)

When you get right down to it, authors do make money from used books. They don’t make it directly, but the fact that a used book can be resold to get back some of what was paid for it is taken into account by paper book pricing these days. People are willing to pay as much as a new paper book costs because it has resale value. And in order for it to have resale value, there has to be a way for someone to buy it, and the people who do buy it don’t have any reason to feel guilty—just by doing what they do, they help to inspire the person who originally did buy it (in a form that did pay the author) to do so.

The whole reason people find the publishers’ agency-priced e-books too expensive is that they cost the same amount as Amazon sells a new paper book for, but without the resale value the paper book has. That’s the whole reason paper books are selling so well at this point—if all else is equal, people will buy the one they can turn around for a partial refund if they don’t like it.

I also didn’t notice anything in Lamb’s blog post about how Amazon is itself one of the biggest used-book stores as well as the biggest new-book store, and for much the same reason—excellent selection and low prices. I know my parents rarely buy any book new, because they can usually find it less expensively used via Amazon and they don’t even have to leave their home to get it.

Used-book sales don’t make the author any money directly, but they help form the foundation of the market that is the reason new books can cost so much. Without that secondary market, you wouldn’t find many people willing to pay so much. As Lamb herself notes, we’re seeing that now, in the way that big publisher e-book sales are declining under agency pricing. People just aren’t going to pay as much for an e-book they can’t resell as for a paper book they can.

And that’s why those other writers are happy used books are selling. They show that there’s still a market for their paper books—at the same time as they help make that market possible.

(We previously covered a post by Lamb in 2012 about five mistakes that are killing traditional publishing.)

When I first spotted the post, I thought to myself: Man, this is either a post begging to be misunderstood or pure clickbait. But no matter, I CAN understand what Lamb is saying but the very long rant cannot disguise her irritation that she was being denied profits by people going to used book stores.

Writing a post that will probably alienate readers is probably not going to endear you to folks, but I respect Lamb for putting it out there anyway.

I’m an author myself. Of course I’d like to earn money from my work. But I have to say I derive more pleasure from having my stories read. I remember my cash-strapped days where a used bookstore was my salvation. And her recommendation that a reader should buy an ebook to support the author? Look, only folks from rich countries can do that. As much as we’d like to support our favourite author, not every reader in the world can do this.

In Malaysia, buying a book is like an American buying a book for $30-$100. It’s THAT expensive. Used bookstores came to our rescue. (Now, if she hates used bookstores, wait till she visits some of our rent-a-bookstores where shop owners rent books for a few dollars each time.)

Fortunately, indie books remain affordable, so many of us would try to buy an ebook if we could, but ebook technology is, again, only for the well-off as each device can cost up to a quarter of a month’s salary for some!

Good arguments over a contentious issue!

I would point out that the cost that authors pay for used book stores isn’t equally shared. Popular books that have been out several years are easy to find online or even locally. New books and books that sell modestly are harder to find, so people who want them are more likely to buy them rather than wait.

That means used books are more likely to take sales away from authors who’ve been earning an ample income for years and least likely to hurt new and obscure authors. Even that well-established author can benefit from used sales. When readers discover that they like an author through a used book, they’re more likely to buy new their more recent books.

Remember, the chief problem that almost every author faces is visibility. People who’ve not heard about your or your books aren’t going to buy them. A used book at a modest price may not earn its author any money, but it does introduce them to readers and give them visibility. That’s worth something.

—–

I might add that I never bought the argument of Google’s lawyers that when it posted books online without the author’s permission it was helping the author get later sales. Not so, I thought. Buying used books reminds readers that books ought to be paid for. Google’s scheme teaches a certain sort of people that books don’t have to be paid for, which is completely different.

Amazon and Google have different but equally depraved business models about books. Amazon’s model is to squeeze suppliers, meaning authors and publishers. That’s why in many cases it pays ebook authors half what Apple’s iBookstore pays. That’s Bezos telling authors, “Go starve. We are Amazon. We don’t care.”

In contrast, most of Google’s business model is built on making money from exploiting without payment content created by others. For webpages, that’s fine. People post to be read, so Google search is doing them a favor. But for books, authors write to sell their books rather than merely to have them read alongside paying ads. Google was way out of line to assume that everyone’s business model had to align with theirs.

Somehow, I doubt the executives of either company lie away at night pondering how they could help authors earn a decent living. Their profits are the only profits that matter.

–Michael W. Perry, co-author of Lily’s Ride (adapted from a bestselling 1879s novel)