Please don’t get the wrong idea from this headline. I’m not advocating the elimination of printed books from our homes. I believe that print belongs on our shelves and probably will always be there. But I’m moved to this confrontational headline by another piece of snark that, as so often, recklessly conflates lack of print with illiteracy, and implicitly equates Kindles with Ray Bradbury’s book-burning Firemen in Fahrenheit 451.

Please don’t get the wrong idea from this headline. I’m not advocating the elimination of printed books from our homes. I believe that print belongs on our shelves and probably will always be there. But I’m moved to this confrontational headline by another piece of snark that, as so often, recklessly conflates lack of print with illiteracy, and implicitly equates Kindles with Ray Bradbury’s book-burning Firemen in Fahrenheit 451.

Stephanie Cohen is moved to ask “What Happens When Homes Have No Books” in Acculturated by a recent article from Carol Rasco, President of Reading is Fundamental, which states that “two-thirds of the country’s poorest children don’t own a single book.” To her credit, Rasco takes a far more engaged and activist stance, emphasizing that “Access to Books Is Critical to Ending Illiteracy.” Cohen, though, takes a more elegaic tone, bemoaning “the disappearance of held objects of cultural and education significance.” She approvingly quotes another article from the New York Times – hardly the most neutral forum in the pro-versus-anti-ebook debate – to the effect that “in our digital conversion of media…physical objects have been expunged at a cost … the loss of print books and periodicals can have significant repercussions on children’s intellectual development.” (Actually, ebooks can have positive repercussions, but for that, see below or here.)

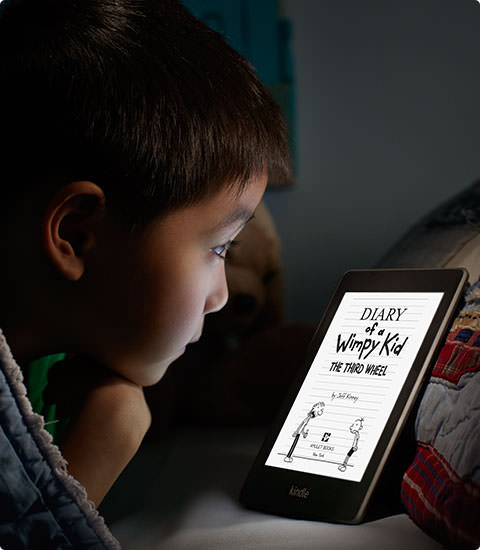

Books are not “held objects of cultural and education significance” – they are read objects, or they are just so much paper. A Kindle, or even a smartphone with ebooks on it, is arguably a held object “of cultural and education significance.” And you only have to go into any of the bookstores whose demise Cohen evokes to see shelves crammed with books of zero cultural and education significance, stuffed in there by publishers.

Right now, I’m reading Robert Rait’s The Scottish Parliament before the Union of Crowns on my held object of cultural and education significance. Never going to be the most popular title, right? Nor the easiest to come by in your average bookstore. Before the advent of digital, I’d have been lucky to have even known it existed. Yet thanks to the miracle of Kindle, I was able to download it, and now carry it around with me wherever I go. Vade mecum. Even if I’d ever gone for a print edition of it, before the advent of ebooks, I doubt I’d have found one compact enough to lug around. And if anyone wants to delve into the intricacies of Scottish constitutional history, they’re welcome to test my comprehension and retention levels on the topic, from the etext, versus print. What, no takers? Thought not. So much for the dumbing-down impact of ebooks.

But I guess Cohen doesn’t want to take on board studies like the recent one by the UK’s National Literacy Trust (“dedicated to raising literacy levels in the UK” and every bit as committed as Rasco) which shows that ebooks actually help motivate kids to read, and benefit child literacy. She quotes one of Bradbury’s characters, who states that “books were only one kind of receptacle … the magic is only in what the books say” – then dismisses him as a coward. She’d rather use America’s shameful literacy levels as a stalking horse for the digital-versus-physical debate. And that conflation does no service to either.