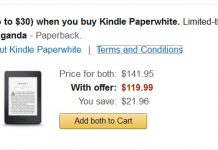

I’ve spent too many days this summer visiting this page on Amazon’s Kindle store, waiting for the price of the latest book from Charles Stross to drop to $9.99 (as of the date of this post, it’s $11.99). Clearly, it’s not going to happen until the publisher feels it’s notched as many $12 purchases as it can from eager fans who aren’t as price-conscious as I am.

But wait a minute! I too am an eager fan, and because of this pricing issue, I ended up reading the book for free. I’m still a fan but now I’m no longer a potential customer. The publisher lost the author an easy sale.

I bring this up not to post yet another gripe about agency pricing, but to suggest an alternative strategy, one that might help the publisher and author earn more money but that would also benefit casual fans like me.

Sometimes I get the sense that publishers think I’m looking at all formats at the same time, then making a decision about which one to buy. But that’s not the case at all; I’d say this is a more accurate profile of me as a book consumer:

- I buy >95% of my books digitally now, and save my print purchases for special items (e.g. art books, gifts, out of print and used).

- I’m never a superfan, hardcover collector, and general fan at the same time for the same title/author, so it’s unlikely the publisher can force me into a higher spending bracket by limiting purchasing options.

- When I decide to pay more than $10 for an ebook, it’s usually for emotional reasons, not simply because it’s a new release; scarcity has a weaker influence on me in the digital space.

- Publicity, marketing, and the social aspect of reading all help build up a desire in me to purchase a book as soon as it comes out, not in six months. However, due to the points listed above, I’m generally unwilling to pay a 20-40% “new release” premium for an ebook.

I think the publisher missed out on two things by pricing the book at $12. First, by not lowering the price to that magical $9.99, it lost at least one sale from an eager fan who was more than willing to buy the book immediately. That argument about cheap ebook prices eating into hardcover sales doesn’t apply to me, because I would have never bought the hardcover in the first place no matter what it cost–this isn’t the sort of book I want as an heirloom or physical object.

Second, I don’t think the publisher maximized its potential revenue from those superfans who can’t wait to read an author’s latest book, and who aren’t nearly as price sensitive as casual fans like me. I know from reading the author’s blog that he had a draft of this book turned in nearly a year ago, well before the original deadline, and that subsequently the publishing date for this title was pushed up by several months. This seems an easy win for the publisher: offer exclusive early access to the latest title in a series for a premium price. Instead, Penguin only priced the ebook $2 higher than “normal” Kindle prices and stuck with a traditional release window. I think superfans would have been willing to pay far more for immediate access–especially if the book wasn’t available anywhere else at the time.

Based simply on my own buying behaviors, here’s how I’d sell books these days:

First, I’d collect all those high-value sales up front by releasing an “exclusive preview” ebook edition for $20 or more before the hardcover comes out. I might include a special preface from the author, or deleted chapters, or editor’s notes–something to give it the stink of premium and further entice superfans.

I’d release the hardcover next, at least a month after that exclusive preview edition, at standard hardcover prices. I’d make sure it looks nice and is well made, because the people who buy this are buying it for its physical qualities as much as for what’s printed on its pages.

At the same time, I’d release the standard ebook at that magical $9.99 price point that makes readers like me hit the “Buy now with 1-Click” button without hesitation. I’d skip that $12-14 price point; it makes the publisher look greedy (yes, I know, publishers hate it when customers think that way, but it’s How Things Work), and it drives away easy sales from readers like me. That exclusive ebook edition would have already captured the superfans’ dollars, and casual fans would never buy the hardcover anyway.

Adding a $2 “new release tax” to an ebook just kills the sale–and in 2010, you’re not only losing customers to libraries but also to pirated versions of those ebooks. I checked: yes, the title in question is already available in pirated format as well as library format. It takes nearly the same amount of time to download a pirated copy as it does to buy a legitimate copy, which I think drastically reduces the ability of a publisher to use scarcity to force hardcover/”new release ebook” sales. Ebooks in general really wreak havoc on that whole scarcity thing.

Maybe I don’t fit the average consumer profile, I don’t know. But I do know that if publishers offered more targeted price points at the right time in the release cycle, they’d get me to spend a lot more on books.

Your posting sounds a lot like Baen.

They sell advance reader copies several month prior to the hardcover being published at a premium price ($15) for fans that want to read the new book *now*, new releases mostly at similar or lower cost then the paperback ($5-$10), and backlist titles in the free-$5 range.

I’d have to say at this point they’re also almost the only digital publisher who has gotten any money from me. Above their price range, i’ll get it from the library and read it for free.

I like the idea of an early preview edition with special features. But I think you are over-complicating things a little. The problem is that right now, long-time customers like you and me simply don’t trust them because we feel they are playing games with us. If I could feel assured that (for example) the price would reliably be lowered on a consistent basis when the paperback version comes out, I would have no problems with paying whatever the new release price is if I really wanted it as a new release. Where I get worried is when a book is released at $14.99 and never, ever goes down—even when $7 paperbacks are available at the bricks and mortar store. Then I feel like they are playing games with me, I resent that, and make other plans to read the book (library, etc.)

I agree with you though that many ebook fans were never going to buy the hardback in the first place. The whole ‘cannibalizing’ argument is ridiculous.

Yes. I definitely cobbled together the post from the ideas of dozens of smarter people, but particularly I was combining thoughts on Baen, the Connect with Fans + Reason to Buy model argued by Techdirt, and chapter two of the “The Undercover Economist” (which talks about price targeting).

The only way a publisher is going to get me to buy more books is if they start pricing their ebooks to be less than the discounted price of their mass-market paperback on the same site (Barnes & Noble).

Great post. This is how I also think ebook sales should work. However that magical price point for me is $1-2 below the mass-market paperback price or $4.99 (I prefer the $4.99 price or below, I usually don’t buy higher than that). I get most of my books through my library system, either ebook, audiobook, or physical book if I have to. I only buy books I can’t get through my library or that I appreciate enough to have in my home library. I buy most of my physical books second hand.

I’m with Bruce and Clara, I’ve never paid more than $6 for an ebook, and that was rare. Most of my ebooks are either free or low cost indies for $2.99 or less.

If the ebook price is ridiculous, I get the physical book used (Nora Roberts, I’m talking to you!). I will not play their game, therefore, they don’t get money from me.

My biggest wish for the Kindle is the ability to read the library formats.

I also frequent our library district’s semi-annual books sale. After the first day of the sale, you can get books for $5 a box or bag. It’s a great deal!

As Joanna mentions. One of my biggest problems is when they try and sell an ebook for far more than the pbook.

As an example; Naamah’s Kiss by Jacqueline Carey came out as a $7.99 mass market pb at the beginning of June yet the ebook price has remained $12.99 which is what the publisher had it priced when the only paper version was in hardcover. Ideally the ebook would be $5.99 or $6.99 at most right now, or at worst $7.99

I must confess the publishers have actually instilled a real animosity in me. When I first had my Kindle, I bought quite a few $9.99 new releases from known authors I had enjoyed before. Since the agency pricing, I put a hold on anything like that at the local library. I won’t buy books in paper, and my ebook buying is pretty much in the less than $7 range and less than $5 a lot of the time. To my own surprise, I’m even getting the newest books by long time favorite authors whose previous books sit in rows on my shelves from the library. There’s a vague thought in the back of my mind that someday I’ll get the Kindle version of those book when the price comes down, but will I really?

Making customers really, really angry isn’t the greatest way to save failing businesses.

What really frosts me is when the Agency 5 CEOs talked about ebook pricing when they switched to their new contracts, they pretty much all acknowledged that ebooks should cost less than their paper counterparts (Simon & Schuster’s Reidy commented that they would probably end up $1-2 less than paper), yet they are still leaving the ebooks priced up at hardcover/trade paperback prices after the lower-priced mass market paperbacks come out. They may discount the price of the ebook when there’s a hardcover or trade PB, but not when there’s a mass market PB. If you try to complain to a retailer, to see if they could nudge the publisher because the price of the ebook is greater than the MMPB, they just do the equivalent of a shrug because it’s the publisher setting the prices.

Also, why aren’t these ebooks priced the same everywhere? With a paper book, there’s a list price and the retailer can discount, or not. What is going on when the ebook price is set by the publisher, and at Amazon and B&N the price is $7.99, but at Sony, the price is $8.45? Is there really a list price for ebooks?

Bruce it is clear that the Publishers are milking the last possible super profits out of the embryonic eBook market for as long as they can. There is no doubt prices will drop as the eReader market expands beyond the high spending early adopters. As many threads on this site document, this is driving more people to the torrent sites and once that process starts it is very hard to slow it down. I have seen it happen myself.

Personally I do hope that eBook prices are not the same everywhere – because that smacks of price fixing and that’s definitely NOT in the interests of readers. eBooks should be sold to eRetailers at a wholesale price and the eRetailer should be free to sell at whatever price they choose.

This is great; by not buying an ‘overpriced’ ebook Mr. Walters is proving the point that if consumers don’t like the price of the supply, the demand will drop.

Howard,

With the Agency Pricing model, the publisher is setting the price, and the retailer is just their agent who gets a percentage of the retail price. So, if the agency publishers’ prices at one retailer are consistently higher than at another, what’s the real MSRP for the ebook? Is it cheaper because one retailer is getting a higher agent fee, or is the publisher favoring a particular ebook format because the DRM cost is cheaper for that ebook format? Or for that matter, why are the Agency 5 publishers doing special free or reduced price ebooks at one retailer and not the rest?

At least with paper books, you know that certain books are discounted because the retailer is selling it as a loss leader, or because they are selling remaindered books, or they are selling those specialty press coffee table books which have a huge MSRP but are in reality going straight to the clearance tables.

Bruce that is just like any other product then. Producers do deals with retailers on volume, discounting, promotions etc. Bigger volumes produces lower bulk pricing. The important thing for readers/consumers is that eBooks are made available to multiple retailers and that they cannot fix the selling price which must be chosen by the retailer. This competition is what we need and what the anti trust people must push for.